Those quaint foreign gear-changing devices - early British adaptors of derailleurs

Posted: Monday 21st September 2020

The British club cyclist’s antipathy to derailleurs until after World War Two is well documented in Frank Berto’s magisterial tome The Dancing Chain. This was the era in which the fixed gear was the norm. If any gear was used it would be a hub gear. Gordon Selby in his history of Cyclo provides an account of the struggle that Louis Camillis, the founder of British Cyclo, had in getting his products accepted (1). There was a widespread prejudice amongst many of the principle writers of the day, e.g. F T Bidlake, against the chain running out of line. One of the foremost touring writers of the day was Wayfarer whose doctrine of “as little bicycle as possible “ discouraged anything more than having two single sprockets either side of the hub.

One of the consequences of this was the invention of the Trivelox in 1931 in which the lever moved the sprockets into line so chainline was always maintained. The Trivelox was initially only fitted to Triumph Cycles (the company the inventors were working for) but it soon became available to other makers and was very popular especially fitted to tandems. Its main drawbacks were additional revolving weight (400g heavier than a Sturmey) and the rapid wear on the hub spines.

I had always assumed the derailleur as a French invention, thus I was surprised to discover the first practical derailleurs were British. These were the Gradient and the New Protean, both launched in 1899. The latter was fitted to Whippet cycles and in France came to the attention of Velocio who, before the word derailleur was coined, referred to all change gears as ‘whippets’. In the CTC Gazette in the latter part 1900 there are a number of letters praising these gears:

“my experience is that I do not get up the hills if they are short as quickly as my companions on fixed wheel but the exertion is less, I am much fresher at the end of a day’s run. I calculate I am about two miles an hour faster than on a fixed wheel.”(2)

Although reception was initially favourable these gears were criticised often on aesthetic grounds and by 1903 they were ignored and soon forgotten by the cycling press. The patent was sold to the French maker Terrot and when it was commented on by British writers it was described as a French invention!

This article explores those pioneering and maverick British cyclists who before 1930 embraced the use of derailleurs. This is one of the rare instances where cycle tourists led the way. No racing cyclist in Britain before the mid 1930’s used a derailleur in competition, in fact it was the Australian racer Hubert Opperman who was the first to use a derailleur. One of the earliest adaptors of variable gears, specifically the floating chain system, was Vernon Blake. Blake adopted the floating chain after meeting Paul de Vivie (Velocio) around 1911. Velocio trialled bi-chains, the first front mechs and numerous variable gear systems, or as he called them “polymultiplication”. Le Chemineau rear gear made from 1911 to 1949 by one of his cycling companions Joanny Panel was his invention. Velocio also invented the design of the Standard Cyclo which led to the creation of Cyclo by another of his followers, Albert Raimond.

The floating chain systems as used by Blake features a triple chainring and single freewheel on each side of the rear hub. A steel pulley was fitted to the rear drop-out which was needed to prevent the chain coming off when in low gear. He also fitted a couple of chain guides to the chain stay. Down changes were made with the toe and up ones via a small metal hook used to pick up the chain. Blake became very expert at this and could make changes at speed. (3). He had a solution to one of the problems encountered by modern mountain bikers when using the small chainring in very muddy conditions: that of ‘chain suck’:

“A muddy chain often refuses to fall away from the smallest chain wheel and is carried up again on the back half of the chain wheel. This difficulty is easily got rid of by placing close to the side of the chain wheel and under the bracket at the point the chain should detach itself, a small crescent shaped piece of metal (he christened this a ‘décrocheur’ from the French verb to unhook) which throws the chain off should it start to stick.” (4)

In Cycling December 4th 1919, Blake explains how Velocio had given up on the floating chain because of this problem. Blake feels it is necessary to explain why the chain will not fall off when in a lower gear and how you can change whilst riding. He admits to the impossibility of avoiding oily fingers but points out that some ‘flottantées’ use a piece of wood about a foot long to enact a change (rested on the handlebars when not in use and place an aluminium hook over the large chainring to prevent the chain over-shifting and jamming between outer ring and crank. He says it is necessary to have two wire guides running from the seat tube to prevent the chain unshipping when changing down. We often think of Cycling as very conservative, the voice of the cycling establishment, yet they gave a great deal of space to Blake’s outlandish ideas.

Not surprisingly the floating chain was not seen as a feasible option. The only other British user I could find was one Medwin Clutterbuck who, writing in Cycling in 1930 (5,) said that changing using your toe was a simple matter and that using the hook to change up prevented dirty hands. Medwin adds that the hook could be carried in the end of the handlebars when not in use. For Britain he was using ratios of 72, 60 and 45 and 65, 54 and 40 but recognises that for Alpine conditions he would need to gear down to about 32.

Many of the earliest users of derailleurs were regular visitors to France. Possibly the earliest was A W Rumney, editor of the CTC Gazette (1907-1913). A widely travelled cycle tourist and advocate of low gearing, writing in Cycling in 1921 in his regular column “The Rolling Wheel”, Rumney claimed that by using a six-speed variable gear it would:

“Enable a nonagenarian to climb Westerham Hill sitting up and smoking a pipe” (6)

In the early 1920’s he used a two-speed French gear curiously called L’A’s, which as the gear change was made by back pedalling had the advantage of simplicity, not needing a cable or lever. In addition to the L’A’s back pedal changer with a double chainring (giving four gears) he had an F.W. Evans fitted with a Chemineau 3-speed, (similar to a Standard Cyclo) with gears of 78, 62 and 44 (7). Such was the novelty value that in 1924 it was on display for several months at Evans London shop.

Only a very small number of tourists such as Cliff Pratt, the founder of the York Rally, and Neville Whall (who used the pseudonym Hodites, Greek for wanderer), who led CTC continental tours, had variable gears. Pratt starting using a Cyclo in 1929 which he obtained from Camillis. He describes in his autobiography Sixty Six years a Cycle Tourist the prevailing attitudes of the time:

“29 November 1929 must be regarded as a red letter day as I had my first derailleur gear fitted, revolutionising my activities. Of course variable gears had existed for some time but the club fraternity had decided that the Sturmey was not acceptable. no self respecting clubman would dare turn up on a run with a Sturmey” (8)

F.W Evans was the pioneer in the trade, advertising in the CTC Gazette the Standard Cyclo and a fitting service as early as July 1929. 1930 seems to have been a pivotal year in the acceptance of derailleurs with far more positive press coverage. That year’s review of the French show has a far more receptive note when discussing variable gears (9). Bidlake, one of the authoritative figures of British cycling, wrote in his regular column ‘The Rolling Wheel’ a positive report on a friend’s conversion to this type of gearing (10). He even goes so far as to admit hub gears may have more friction. Coincidently, 1930 was also the year in which both Vernon Blake and Velocio died.

Cycling recognised the growing interest in this type of gearing by featuring a two-page article by their technical writer Videlex, as he puts it:

“A clear exposition of the chain jumping system which is becoming more popular every year this side of the Channel” (11)

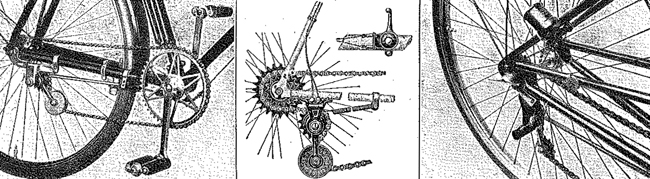

Videlex describes as two bogies that of chain misalignment and the chain can be damaged by moving across the cogs. The article is illustrated with three gears: the Cyclo, L’Izoard (shown fitted to a Saxon tandem) and the Perry, which looks to me to be British Cyclo copy. The use of these for tandems is strongly advocated. A great deal of space now begins to be devoted to advising riders on how to convert their existing machines and educating builders in the need to change their design, principally by widening the rear drop-out. For the first time in 1930 Brown Brothers featured derailleurs in their catalogue. Half a page featuring the Perry and Cyclo and a special hub described as with extra long collar (I assume a greater depth of threads for the freewheel) (12).

The Great Depression slowed down the use of derailleurs as they made machines more expensive than if just fitted with a single gear. At this time Sturmey Archer were the dominate force in gearing and it would be natural for a British cyclist think of them if planning to use variable gearing. The first large manufacturer to offer a derailleur as a standard specification was BSA in the mid 30’s with their Opperman Special. So there was a gradual acceptance of derailleurs in Britain. That this happened is due to the work of the subjects of this article.

References

1. Gordon Selby; History of Cyclo The Boneshaker no.165 Summer 2004

2. Letter in the CTC Gazette August 1900 p398

3. Frank Berto: The Dancing Chain 3rd edition 2009 pp64/5

4. Vernon Blake : CTC Gazette October 1913

5. Medwin Cluterbuck letter in Cycling 25/41930

6. A.W. Rumney: Cycling 1st December 1921

7. A.W. Rumney: 50 Years a Cyclist. Published 1928 p61

8. Cliff Pratt: Sixty Six Years a Cycletourist p5 Pentland Press 1994

9. Cycling Review of the French Show Cycling 14th November 1930

10. F.H. Bidlake: Cycling 8th April 1930

11. Videlex : Cycling 11th April 1930

12. Brown Brothers 1930 catalogue p145

Posted: Monday 21st September 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.