Competitive Cycling in Apartheid's Shadow

Posted: Saturday 22nd August 2020

An Historic Cycling Event in Natal Province in the 1970s

Early one misty October morning in 1974, a small group of cyclists and officials gathered unheralded by the roadside in the dusty Natal south coast sugar belt town of Umzinto some 20 kilometres inland from the small coastal resort of Park Rynie. It was the start of a road race which would follow a ruggedly hilly 160 kilometre route into the elevated interior through the villages of High Flats, Ixopo (the rural setting for Alan Paton’s novel, Cry the Beloved Country) and Richmond to finish in Thornville some 20 kilometres outside the provincial capital, Pietermaritzburg.

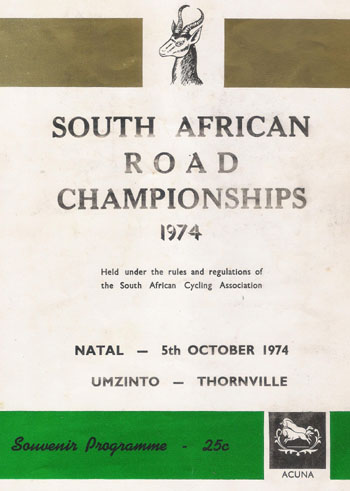

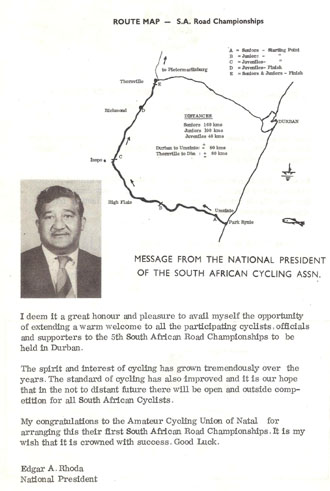

This event was the1974 national road race championships, with seniors riding the full distance, juniors 100 kilometres and juveniles 40. But what made the event truly historic, as the official race programme declared on its cover, was that it was ‘Held under the rules and regulations of the South African Cycling Association’ (SACA). This was the first time that SACA had held its annual national road championships in Natal and the fifth–ever staging of the event. What this choice of provincial venue tacitly acknowledged was the spontaneous flourishing of cycle sport amongst Natal’s, and particularly Durban’s, Coloured community in the early 1970s. This was because SACA and its local affiliate, the Amateur Cycling Union of Natal (ACUNA), while being non–racial in terms of their written constitutions had de facto memberships consisting predominantly of Coloured people(2).

That the race’s chosen starting point was near to Park Rynie was a further indication of this because, in terms of apartheid zoning, a section of this coastal resort town had been designated for ownership, occupation and use by Coloured people. Thus event competitors, officials and supporters, particularly those who had travelled from other provinces, could readily find suitable accommodation conveniently located nearby – something which apartheid restrictions elsewhere in Natal precluded as other resort facilities set aside for Coloured people were non–existent.

These 1974 SACA national road championships attracted competitors from many different parts of South Africa who had travelled long distances by road to compete. The official programme lists the names of riders selected to compete in the event from various provinces along with their representative colours (3) .

- Natal (black and white)

- Eastern Province (black and red)

- Griqualand West (peacock blue and white)

- Western Province (royal blue and white)

- Border (brown and white)

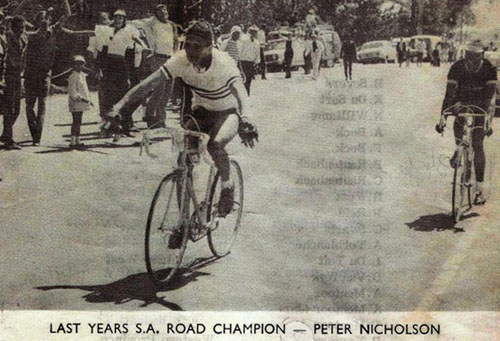

Surprisingly, there were no riders representing either the Transvaal or Boland – the latter being particularly curious as the Paarl area had the reputation of being a great centre of cycling amongst the local Coloured community to the point of being literally the cradle of Coloured competitive cycling in the country. However, the race programme did list individual entrants from the Yorkshire C.C. (including the defending senior champion, Peter Nicholson) and this was a leading club in the Boland region. Why no Boland representatives were selected remains a mystery as does Nicholson’s appearance in the Yorkshire club’s colours since he is listed as having won the 1973 event riding in the colours of the Border region.

In any event, the challenging nature of the hilly course took a heavy toll on the riders particularly in the senior event which only a few of the 20–odd starters completed, with Nicholson winning from Bill Newman of Western Province. In the junior event, Ernest Hartell (Natal) won from J. Masseli and W Erasmus, both from Western Province. The juvenile event was a clean sweep for Natal riders, with Rodney Isaacs (Albion C.C.) winning from Shaun Thring (Bayview Wheelers) and Kevin Matthews (Liberty Wheelers). The results in these latter two youthful categories strongly suggested that ACUNA riders were definitely an emerging force in SACA cycling.

‘Race’, Apartheid and Organised Cycle Racing in the 1960s and 1970s

However, while the 1974 SACA national road championships attracted little publicity at the time, the same cannot be said for another cycling event held earlier in the same year. This was the second ‘Rapport Toer’ stage race, run annually between Cape Town and Johannesburg and won on this occasion by the British rider, Arthur Metcalfe (4). This locally much publicised event was jointly sponsored by Rapport, an influential Afrikaans language national Sunday newspaper and the apartheid state in the form of its department of sport. The event involved specially importing riders from Portugal, Italy and Britain who rode in unofficial national teams wearing the colours of local sponsors as well as several sponsored South African teams including, significantly, a separate team of African cyclists(5). However, no local Coloured cyclists participated in either the 1974 Rapport Toer or the inaugural event in 1973.

The reason for this was simple: the Rapport Toer was held under the auspices of the South African Cycling Federation (SACF) – the cycling body historically associated with white organised cycling in the country. In the late 1960s the newly established SACA – the explicitly non–racial but predominantly Coloured cycling body – had from the outset distanced itself from the SACF, hence the absence of any of their affiliated riders from the Rapport Toer.

The twists and turns of South African cycling politics during the 1960s and 1970s were Byzantine in the extreme. During the 1950s, the historically white SACF had enjoyed exclusive international recognition by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Empire Games Association. As a result, white South African cyclists and officials, all affiliated to the SACF, enjoyed unrestricted international participation both at home and abroad. Several SACF riders even won medals at Olympic and British Empire games in the 1950s. During this period also, SACF–sanctioned stage road races began to proliferate at home, including events between Johannesburg and both Durban and Cape Town which were precursors of the Rapport Toer.

In the early 1960s, however, as the state’s racially exclusionary apartheid policies extended increasingly into the sporting sphere, international as well as internal opposition to sporting apartheid rapidly gathered momentum. The 1960 Olympic Games in Rome proved to be the last time that South African cyclists were allowed to compete in these until the post–apartheid era of the 1990s. In 1970, the UCI suspended the SACF sine die, effectively closing the last portal to international competition for white South African SACF–affiliated cyclists. At the same time, however, the UCI failed to admit either SACA or any other South African cycling body to its ranks, thereby effectively isolating all local cyclists internationally.

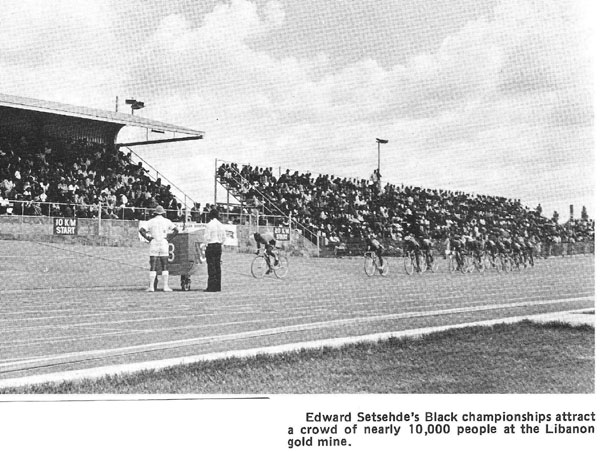

It was against this background that the Rapport Toer was instituted in 1973 as an exercise in ‘sporting sanctions busting’ – a practice already evident in major local sports like rugby and cricket. As to the presence of teams comprising African cyclists in successive Rapport Toers, they were recruited from the South African gold mines where cycling was well established as a segregated sport, with most mines having cycle tracks adjacent to the miners’ hostels. At the time, most of the mineworkers were migrants from neighbouring African countries and that several of those who competed in the Rapport Toers of the early 1970s went on to represent countries like Botswana in international cycling competitions testifies to this (6). In short, while these riders were certainly African, they were not South Africans – a fact which was conveniently glossed over by the race organisers. Throughout, the claim was made that the racially–heterogeneous fields of the Rapport Toers demonstrated the commitment of the SACF to eliminating apartheid in South African cycling. However, this failed to resonate in international cycling’s corridors of power.

Thus, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, organised cycling in South Africa became increasingly isolated internationally and simultaneously internally polarised on racial lines. On a local level in Natal province, however, and particularly in Durban new developments in the sport were taking place.

The Explosion of Competitive Cycling amongst Durban’s Coloured Community

In the early 1970s, white competitive cycling in Natal had reached a low ebb in the wake of international isolation, with Durban and Pietermaritzburg being reduced to having only one cycling club each, both affiliated to the Natal Cycling Union (NCU) which in turn was a subsidiary of the SACF. Despite this, white cyclists in the two cities had unrestricted access to purpose–built local cycle tracks which, in terms of apartheid legislation, were reserved exclusively for use by white riders, officials and spectators.

In contrast, by 1975 ACUNA, with a predominantly Coloured membership, had seven affiliated cycling clubs. In Durban there were four (club colours in brackets):

- Liberty Wheelers (orange, blue & white)

- Bayview Wheelers (green & orange)

- Alpha C.C. (red, yellow & black)

- Vigilante C.C. (red, blue & white)

In Pietermaritzburg, there was Albion C.C. (colours: black & yellow). In addition, there was Steigers Wheelers (colours: plain white) in Escourt, Northern Natal. Also affiliated to ACUNA was Omega Wheelers which claimed to be ‘…the first all–ladies club in the country’. However, in the early 1970s, none of these clubs had access to a cycle track. Despite this, it was noted that at SACA national track championships held at venues in other provinces, ‘The first Natal track team (April 1973) brought home 1 silver medal, the 1974 team brought home 2 gold, 2 silver and 5 bronze medals (this without track training)’ (7).

Clearly, Coloured people in Natal and especially in Durban had been gripped by an enthusiasm for competitive cycling and had set up the requisite structures to independently pursue this. Evidence is of entire families, streets and indeed whole neighbourhoods in segregated apartheid era Coloured communities becoming cycling enthusiasts. For the most part, it was the teenage sons who were the competitors in families while their fathers and uncles were the officials and their mothers and sisters the administrators. Younger children were also swept up in the new enthusiasm, with many boys aspiring to follow in the racing footsteps of their older brothers once they were big enough to have racing bikes.

Local cycle shops were quick to recognise these new developments as demand for racing machines, both road and track, along with racing equipment rapidly escalated. Dealers began to offer support to ACUNA and its affiliated clubs in the form of small racing prizes and bought advertising space in official race programmes.

In the face of these unprecedented developments, local white cc and cycling officials generally remained aloof, monitoring them from a distance. For instance, as the 1974 SACA road race entered its closing stages, leading SACF and NCU officials appeared as spectators in the village of Richmond but made no contact with the race entourage. However, they were about to be overtaken by certain new concessions made by the apartheid state in a further attempt to overcome continued international sporting isolation.

Of critical importance for Coloured cyclists were certain relaxations in the Group Areas Act as this applied to sporting facilities like cycling tracks. No longer were these restricted to use by people of specific ‘race groups’. In 1975, therefore, ACUNA was able to apply to hold training sessions and stage track meetings at the municipal velodromes in both Durban and Pietermaritzburg which had previously been reserved exclusively for use by the white cycling fraternity.

They were granted permission to use the tracks for these purposes only at times which did not clash with their use by their white counterparts and could thus neither train nor compete with them.

An ACUNA printed programme dating from the 1975 provincial track championships held at Durban’s Kings Park track offers some interesting insights into the nature of track racing during this period. The programme lists the following track officials:

- Racing Director: L.G. Clarke

- Referee: D.B. Isaacs

- Starter: K.E. Clarke

- Assistant Starter: D.B. Isaacs

- Timekeepers: M. Williams (chief), C. Williams, E. Williams, M. Cochrane, H. Isaacs, K. Gunther

- Lap Scorer: W. Dusart

- Corner Marshalls: P. Manuel, N. Kruger

- Machine Examiners: N. Williams, H. Isaacs

- Racing Commentator: T.A. Abrahams

- Records Clerk: Mrs. Cochrane

- It then lists the following programme of scheduled events.

1. Senior 1500 metres scratch (two heats)

2. Junior 1500 metres scratch (two heats)

3. Juvenile 1500 metres scratch (two heats)

4. Senior Match Sprint 500 metres (four three–man heats)

5. Junior Match Sprint 500 metres (six three–man heats)

6. Team Pursuit 4000 Metres (juniors and seniors)

7. Senior Match Sprint 500 metres (two semi–finals)

8. Junior Match Sprint 500 metres (two semi–finals)

9. Juvenile 300 metres Sprint (two eight rider heats)

10. Senior Match Sprint Final (ride off for third place then for first and second places)

11. Junior Match Sprint Final (ride off for third place then for first and second places)

12. Juvenile 1500 metres Final

13. Senior 1500 metres Final

14. Junior 1500 metres Final

15. Juvenile 5 Kilometres

16. 10 Kilometres (juniors and seniors)

It was certainly a full programme of events and suggests the participation of a substantial number of participants in all three categories: senior, junior and juvenile (8).

Further Developments in the 1970s

As the decade of the 1970s wore on, competitive cycling became entrenched as an established sporting activity in Natal’s and particularly in Durban’s Coloured neighbourhoods. In Durban, the apartheid state had concentrated the city’s minority Coloured population into several widely separated ‘group areas’ and there was a marked tendency for the different cycling clubs to draw their memberships primarily from certain of these areas rather than others. Thus, for instance, Liberty Wheelers which ‘had pioneered the Union’ (9) was based in the suburb of Wentworth and so were most of its members. Conversely, Bayview Wheelers was seen as a Sparks Estate club.

Competitive rivalry between the different clubs became intense with each having their own much–admired star riders who were role models for younger club members. Thus Benny Severs was the top Bayview senior. In 1974 he was the first Natal rider home in the senior SACA road championship, finishing fourth behind Peter Nicholson. In 1975, at the SACA track championships held in Durban Benny excelled, winning the senior sprint, individual pursuit, 1 500 metres and 20 kilometres titles. Only in the 1 000 metres time trial was he beaten by Nicholson.

Being an equipment–based sport, competitive cycling demands not only a substantial initial outlay to purchase a machine but also continuous costs for maintenance, repairs, tyres and accessories. Most of Natal’s Coloured cycling fraternity were drawn from a stratum of skilled artisans. Even so, they generally earned less than their white counterparts at the time and thus sustaining an interest in competitive cycling placed a considerable financial burden on many of those involved. One solution was to purchase and refurbish second hand racing gear. As a result, a market developed in which machines and equipment originally purchased new, primarily by local white cyclists, were frequently sold on to local Coloured cyclists. In this manner, machines came to pass through several hands with some even acquiring their own pedigrees, particularly if they had been ridden by celebrated riders at some stage.

But second hand equipment and the wear and tear of frequent use creates a frequent need for maintenance work. Since DIY is the least costly, home maintenance of racing machines, including tubular tyre repairs, wheel truing, refurbishing frames and the like became commonplace amongst the local Coloured cycling fraternity. With advice and help from family members many of whom were involved in light engineering, spray painting and other automotive trades, some Coloured cyclists became skilled bicycle mechanics and in certain instances found ready employment in local bicycle shops.

Meanwhile, in the political cauldron that was apartheid South Africa in the 1970s the white SACF continued in its efforts to gain re–entry into international cycling circles but with little success. The internal turmoil which this occasioned in the SACF at the time is hinted at by the fact that, whereas the body continued to elect the same person (J.C. Geoghegan from Natal) as its president between 1961 and 1971, between 1972 and 1981 it had no fewer than three different presidents, each one with a different plan to resolve the issue of isolation (10).

Background to the SACF–SACA Merger

To better understand how deeply international isolation affected the SACF from the mid–1960s onwards and led to its ultimately seeking a rapprochement with SACA it is necessary to understand a little more of the history of both organisations.

The SACF was established in 1955, having previously been a part of the national athletics body (11). From the outset, its members – officials, administrators and competitors – were ‘amateurs’ in accordance with the then–existing Olympic code. However, while most SACF members were in fulltime employment, many were able to effectively combine this with their association with cycling. Some established cycle shops or were employed in these in their home towns while others worked as sports organisers on gold mines; some riders found sympathetic employers who gave them generous time off to train and race while many who spent up to two years doing compulsory military service enjoyed the privilege of being state–sponsored amateurs for the duration.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the SACF’s international orientation was primarily towards the Olympic and British Empire (subsequently Commonwealth) games rather than to the UCI’s annual world championships. The ultimate accolade for both competitors and officials was thus to be selected as ‘Springboks’ to represent South Africa at these games. Furthermore, after World War 2 overseas cycling teams were regularly invited to compete locally against Springbok teams. In 1948, a British track team came out, in 1952 another British track team visited and a third (which included Barry Hoban) came in 1961. In 1962 a Dutch track team visited and in 1965 a German track team toured the country to be followed by a team of Australian ‘trackies’ in 1969. In addition, individual top foreign riders toured at various times including, in the early 1950s, Mario Ghella of Italy (1948 Olympic and subsequently amateur sprint world champion), Keith Reynolds from Australia and Jackie Heid from the USA (12). In 1958, Italians Guiseppe Beghetto (world sprint champion) and Giancomo Zanetti toured successfully. In 1965, Beryl Burton, the British women’s multi–champion visited and impressed the all–male local cycling fraternity in exhibition races. For the SACF these were the ‘glory years’ and a golden age of track cycling nationwide.

However, cyclists of colour in South Africa at the time did not figure in any of these SACF activities. In the Cape, Coloured cycling was loosely affiliated to the SACF but competed separately from white cyclists. On the gold mines, segregated African track cycling flourished independently. In the Durban of the 1950s there were three exclusively white cycling clubs – Mayville C.C (which had sponsored Jackie Heid’s visit), Albion Harriers and Durban C.C. – all attached to the NCU and thus to the SACF. However, a group of Coloured youths formed the Avondale C.C. in the mid–1950s in Durban. It survived for some four years, racing separately from white cyclists mainly on a rough asphalt track at Currie’s Fountain, a multi–sport facility set aside for use by Durban’s entire ‘non–white’ sporting fraternity (13). Then, in the early 1960s the Bayview Wheelers club was formed in Durban in a racially mixed part of the city and involving both Coloured and Indian members. When this neighbourhood was rapidly demolished by the apartheid state and its Coloured residents removed to Sparks Estate, Bayview Wheelers moved there with them.

In the late 1960s, Coloured cyclists, officials and administrators primarily in the Cape became increasingly disaffected with the de facto segregationist policies of the SACF both towards them and to cyclists of colour generally and moved to establish SACA as an independent non–racial national cycling body. This in turn led to firmer links being forged with similar incipient initiatives in other provinces, including ACUNA in Natal, and laid the foundations for the cycling boom of the 1970s. As a result, SACA cycling rapidly became self–sufficient, holding its own national road and track championships and quite capable by virtue of its growing membership of sustaining itself independently of the SACF.

For the SACF, however, the 1970s were troubled times as international isolation undermined the progress of its development of the sport. With opportunities for its members to achieve Springbok colours and international success declining rapidly and tours by foreign teams and individual riders ending, competitor numbers dropped and clubs disbanded. For instance, in Natal both Albion Harriers and Durban C.C. ceased to exist. It was in the face of these trends that the SACF embarked on initiatives like the Rapport Toer in the 1970s. However, when these failed to achieve the aim of reacceptance by the UCI, the SACF sought to negotiate further with SACA.

During the 1970s the SACF, dutifully following the convoluted changes in sports policies instituted by the apartheid state in its efforts to overcome continuing international sporting isolation, inched towards the situation which SACA had advocated from the very outset. This was that all cyclists should be free to join any cycling club on their choice irrespective of their racial backgrounds and be able to compete freely together. Once the SACF – following a state directive to all White sports bodies to this effect – adopted this policy, SACA agreed to the possibility of a merger. Both provincial associations and clubs affiliated to SACA were consulted and ultimately the merger took place in October, 1979.

However, there was considerable debate and dissention in SACA ranks before the merger occurred. There were grave suspicions about the SACF’s motives given its previous machinations and also about the terms of the merger – essentially that SACA dissolve into the SACF. At least one club, Albion C.C. in Pietermaritzburg, chose to voluntarily disband rather than join the SACF through the NCU.

The End of the ACUNA Cycling Boom in Natal

With the SACF–SACA merger, the impetus which had previously driven ACUNA cycling in Natal dissipated rapidly. Its officials found that the ‘new’ unified SACF/NCU nevertheless refused to recognise their qualifications and demanded that they write new examinations. Its administrators discovered that certain key members of the old white NCU ‘establishment’ were intent on retaining administrative control of the sport in the province despite outwardly proclaiming a commitment to full racial integration.(15)

Simultaneously, in the new context of open competition its riders found themselves pitted against White cyclists whose unspoken but undoubted advantages included membership of generously sponsored clubs, use of costly cutting-edge racing equipment and exposure to sophisticated coaching methods. All this occurred in the context of a deeply divided wider society in an era charged with racial tension and conflict.

Not surprisingly, many ACUNA officials, administrators and competitors began to lose enthusiasm for the sport in its new guise and, as a consequence, their clubs rapidly lost members and ultimately disbanded. However, a small but determined minority did proceed to join formerly white SACF/NCU clubs and some went on to enjoy considerable success. For instance, Archie Barnwell who had begun racing as a juvenile with Bayview Wheelers joined the sponsored Barlows-Kings Park C.C. (the former Mayville C.C.). He subsequently won a national junior track championship, becoming the first Coloured cyclist to be awarded Junior Springbok colours. Another former Bayview Wheeler who joined Kings Park, Marcel Bengtson, immigrated to Australia where he raced at the highest level and Roland Isaacs became a regular member of the Natal track team.

By the early 1980s, therefore, the ACUNA cycling era amongst Natal’s Coloured community was over. However, in the mid 1980s the Triangle C.C. was established in Durban in an effort to recapture the ‘ACUNA spirit’. Its aim was to encourage youngsters from disadvantaged backgrounds to take up competitive cycling. To this end, in 1990, the club organised a group ride by its members from Durban to Cape Town – a distance of some 1 800 kilometres. At towns en route municipal authorities were lobbied to encourage cycling locally. Nevertheless, it took another decade and the total collapse of apartheid for South African cycling to gain readmission to global competition. The SACA–ACUNA initiative, by adhering to its non–racial principles throughout its existence, undoubtedly contributed greatly to both the development and racial integration of South African competitive cycling. It therefore deserves to be not only recognised but also memorialised.

Footnotes:

- This article is based on a combination of personal experience, documentary sources and conversations with some of the people involved. A member of a leading local cycling family, Hughie Isaacs, recalled historical details and clarified numerous points for me. I am particularly indebted to Archie Barnwell for inspiration and for his guidance on many aspects. Ultimately, however, I am responsible for any inadvertent errors and flaws that the article may contain.

- In apartheid South Africa, people were officially classified as being White, Coloured, African or Indian and innumerable restrictions on movement, association, places of residence, sport and recreation applied to people in the latter three categories. It should also be noted that ACUNA clubs in Durban did have a few Indian and African members, but they were very much in the minority.

- These apartheid–era names for regions have been officially changed and in some cases their borders have also changed in the post–apartheid era. Natal is now KwaZulu–Natal, Border is now in the Eastern Cape as is Eastern Province, Griqualand West (Kimberley area) is now in the Northern Cape, and Western Province and Boland are now the Cape Province.

- ‘Toer’ is the Afrikaans version of ‘Tour’ and is the local term used to refer to the race (which no longer exists). Arthur Metcalfe was a leading British rider in the 1960s who won the British ‘Milk Race’ and rode the Tour de France in 1967 and 1968. He officially retired in 1972 but manufactured MKM framesets which were imported into South Africa. He died of cancer in 2001.

- Riders from Europe frequently chose to compete in the event under assumed names to avoid being sanctioned by the UCI for breaking the sporting embargo. In 1975, the Irish riders Sean Kelly and Pat McQuaid (the present–day UCI president) sought to escape attention for riding the Rapport Toer by doing so but their deception was discovered and both were suspended by the UCI for a period.

- In a revealing passage in the booklet South Africa…where now? by the British journalist John Burns and distributed in 1976 to subscribers to International Cycle Sport magazine, Burns writes in a chapter entitled ‘…The Black Hero’ about the African cyclist Jack Ntseou: ‘In the last two Rapport Tours…he has been the best–placed Black rider…He was born in Botswana (for whom he rode in the last Commonwealth Games…). Six Tswanas working in the South African gold mines…represented Botswana in the Commonwealth Games cycling events in Christchurch’ . (The booklet is not paginated).

- Information contained in a 1975 ACUNA official programme for a track cycling meeting held at Durban’s King’s Park Stadium.

- The printed programme was produced, as was standard at the time, on a stencil on a typewriter and reproduced by roneo. Missing from the programme is a listing of the juvenile sprint final. It contains no list of competitors.

- ACUNA track meeting programme, 1975.

10- More direct evidence of the conflict and acrimony within the SACF at the time is provided by John Burns in South Africa…where now? He quotes Raoul de Villiers, who had served as Geoghegan’s vice–president for four years as saying of him in 1976: ‘I can’t remember his Christian name’. De Villiers was the organizer of the Rapport Toer and was elected SACF president on several occasions in the 1970s.

11- See: W. Jowett (1982) Centenary: 100 years of organized South African cycle racing for further details. I am also indebted to the remarkable powers of recall of Garth ‘Faggi’ Thompson for details of SACF cycling from the 1950s through to the 1970s.

12- An article on Jackie Heid in the US magazine, Winning (February, 1985), states: ‘Heid flew to Johannesburg, South Africa, for three months of racing in cities around the country. “I got a pound a day pocket money, plus expenses,” he said. Sponsoring the trip was the Mayville Cycling Club…He won numerous races in Durban and Port Elizabeth. His name was left on the record books…’ (p.38).

13- Currie’s Fountain was used for athletics, soccer and cycling but the cycling track fell into disrepair. It was also the venue for many political protest rallies in Durban during the apartheid era.

14- The SACF’s various attempts to undermine SACA included the deliberate recruitment of a SACA rider to participate in the 1976 Tour of the Winelands stage race without the association’s consent. SACA and ACUNA members reported being subjected to many slights and snubs by SACF and NCU members down the years.

15- Early in the 1980s, white delegates representing a club with only a few active members succeeded by means of legalistic chicanery in preventing a Coloured man from a club with a large and active membership from being elected NCU vice president. An elderly retired white man who had not been active in cycling circles for many years was elected instead.

Posted: Saturday 22nd August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.