Streamlined 1950s South African trackmen and the 20th century aerodynamic revolution in cycle sport

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

As the bicycle and its rider move forward, the air is disturbed the drag force is highly speed dependent, namely the square of speed. Thus, if we conjure up the parallel with hill climbing, it would seem like overcoming an increasingly steep incline as the speed is increased.

Rob Van den Plas, 1988, The Bicycle Racing Guide (p.97)

Currently, in the early 21st century, aerodynamics is a central preoccupation in competitive cycling on both road and track. Unpaced races against the clock – ‘time trials’ – are contested by pedalling projectiles: skinsuited riders with streamlined helmets crouched low over disc–wheeled, aerodynamically–sculpted low profile machines.

Contrast this with images of leading time trialists from the1950s through to the 1970s: Alf Engers breaking the 50 minute barrier in an English 25 miler; Jacques Anquetil winning the ‘Grand Prix des Nations’ in France. They appear quite conventional in terms of period racing apparel and machines, devoid of helmets, disc wheels, tri–bars and general ‘aero–consciousness’.

The first machine produced for this season by Shorter Rochford had a welded frame built by Barry Chick from Columbus PL tubing with Super Vitus fork blades which were seen as more aerodynamic. This light tubing was usually used for track pursuit style machines or special one-offs. Here of course it would be reserved for short time trials. Alf was able to get away with this as he has a fluid smooth style of riding compared with some with a more punchy style. It would, of course, never be used for explosive track sprinting. The frame was short wheelbase – 36¾” with 75° head and 73° seat angles and is said to have chain stays of 15¾” but images of the frame with the rear wheel almost rubbing the seat tube make one wonder if this is a misprint. The Cinelli fork crown and the front and rear ends were thinned down and reduced to reduce frontal area. The braze-ons were kept to a minimum consisting of gear lever boss, tunnel for gear cable under the bottom bracket and a cable stop under the chainstay for the rear gear.

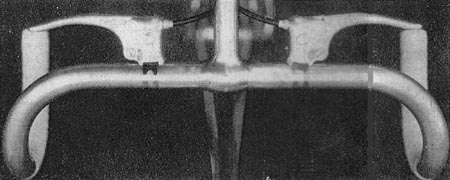

The gear set-up was a composite of Campagnolo lever, thinned down, operating a Huret Jubilee rear mech. which was known for its lightness but even this was polished and pared down. The Campag cranks were slimmed and polished. Even the Campag Super Record pedals had the treatment with the quills removed and the toestraps were cut to the minimum and used with alloy toeclips. In the past the seat pillar had looked like a colander but this time the Laprade pillar was carefully skimmed on the inside to reduce weight whilst keeping a smooth airflow over the surface. These days seat pillars are often aerofoiled to allow the air to ‘slip’ past. The lightest saddle of the day was the Saba which sat atop the lightened seat pillar. The area most responsive to the treatment will obviously be around the handlebar area. The Cinelli 66 bars were slightly shortened and welded and faired into the stem to save weight and improve airflow.

The bars were only taped for a short distance from the ends as there would be no idling along on the tops for this machine. This was quite minor compared with the treatment of the brakes. The levers were moved up almost to the stem and fitted in a reversed position with the levers facing out and sitting snugly behind the bars. Smaller juvenile-size levers were used. The trimmed down front stirrup was positioned behind the fork crown and the cables kept to a minimum. A Weinmann stirrup was used at it took the cable to the side away from the gear lever. This machine was described as having a pair of Super Champion Arc-en-Ciel sprint rims on Omas small-flange quick release hubs with titanium spindles. They were 24 spoke front and rear both tied and soldered and were shod with Clement No. 1 silk tubs. Naturally the bottom bracket had a titanium axle and was made by Omas. Very soon after this machine was commissioned Alf found the weak points. The main one being that he was losing time on roundabouts and sliproads by having to come up from the race position to use the brakes so destroying his hard-earned momentum.

For the mark II bike the brake levers and stirrups were back in the normal position. Alf is quoted: “As I changed for the race I reckoned that all I could do had been done. I taped over the lace eyelets on my shoes as the final touch, and was ready to go.”

Clearly, the intervening decades have seen nothing short of an aerodynamic revolution in the praxis of competitive cycling. Furthermore, it is a transformation which is not exclusive to unpaced time trials. In road racing the norm is now to sport deep section aero rims along with sculpted carbon frames complete with concealed brake and gear cables; track riders in match sprints and madisons employ disc wheels and straddle streamlined machines.

The origins of this post–1970s aero–revolution in cycle sport are directly traceable to two highly–publicised cycling events of the 1980s which dramatically demonstrated its effectiveness. The first was the Italian Francesco Moser’s record–breaking ‘hour’ ride in 1984; the second, the American Greg LeMond’s last gasp overall Tour de France victory on the final stage time trial in 1989.

In 1984, riding at the thin–air altitude of 2300 metres on an outdoor cement track in Mexico City, Moser set a new unpaced World Hour Record of 51.151 kilometres (31.784 miles). In so doing, he not only broke the 50 kilometre barrier but beat the then–existing hour record of 49.431 kilometres (30.715 miles) established twelve years earlier in 1972 by the Belgian maestro, Eddy Merckx, also in Mexico City. But whereas Merckx had done so on what was to all intents and purposes a ‘conventional’ track machine of his era, Moser’s record–breaking steed was revolutionary in several respects. Its novelty lay primarily in both its wheels and frame. Using a large back wheel and a smaller front wheel, the frame – while employing conventional steel tubing – was variously curved to accommodate the different wheel sizes and simultaneously give the rider a lower frontal area.

Complementing this, both wheels were of solid composite construction, devoid of spokes and were termed ‘lenticular’ due to their biconvex lens–like profiles. (Their successors are now generically termed either ‘disc’ or ‘aero’ wheels and generally have thin flat profiles). Clearly, in his preparations for attacking Merckx’s record Moser exhibited ‘outside the box’ thinking in the form of extreme aero–consciousness. While it attracted less attention than his machine, this extended to his apparel which included close fitting shirt and shorts as well as aero headgear and oversocks. Moser’s record–breaking achievement was widely publicised at the time, not least for its revolutionary aerodynamic dimension.

Greg LeMond’s defeat of the taciturn French maillot jaune Laurent Fignon in the Paris time trial stage on the last day of the 1989 Tour de France was witnessed globally by millions on live TV (1). LeMond’s stage win gave him a stunning overall race victory by 8 seconds. But whereas race leader Fignon was mounted on a conventional TT machine of the period (with a sweatband encircling his pony–tailed head and a pair of ‘granny glasses’), the innovative LeMond raced on a low profile machine equipped with a rear disc wheel (but conventionally spoked front), distinctive aero ‘tribars’, a smooth hardshell helmet, skinsuit and curved sunglasses.

The then controversial narrow aero bars gave LeMond a position on his machine akin to the ‘tuck’ position of downhill skiers from whom it was ultimately derived whereas Fignon’s wide ‘bullhorn’ bars rendered him virtually a drogue parachute on his. (Fignon nevertheless finished third in this TT, only 58 seconds behind LeMond whose winning speed was a very rapid 54.5 kph for the 24.5 Km course – a faster average speed than Moser’s 1984 hour record).

LeMond’s Tour triumph served as a decisive further stimulus to the aerodynamic revolution in modern competitive cycling triggered by Moser’s hour record earlier in the decade. But that other competitive cyclists before Moser and Lemond had flirted with aerodynamics is demonstrated by a report tucked away in a 1958 issue of Sporting Cyclist magazine and kindly forwarded to me recently by Classic Lightweights webmaster, Peter Underwood.

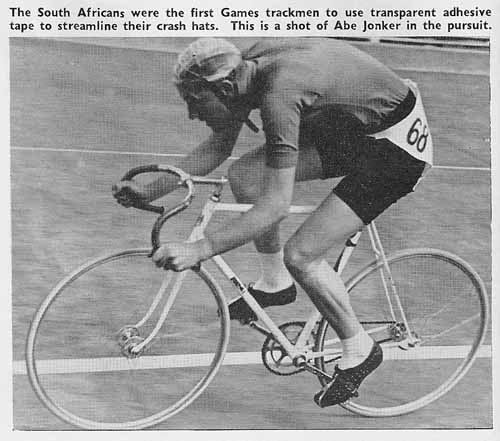

The main photograph in the SC report is of the South African track pursuiter, Abe Jonker, taken at the Maindy stadium in Cardiff, Wales, on the occasion of the 1958 Commonwealth Games. What its caption draws attention to is Jonker’s track crash hat. While of the traditional ‘hairnet’ or ‘Danish’ variety consisting of narrow padded strips, it had been modified by being covered with what the report terms ‘adhesive transparent plastic’, thereby rendering it more aerodynamic.

The accompanying article notes that Jonker’s team mate, Jan Hettema, used a similarly modified crash hat in the 1000 metres TT. Jonker employed his to compete in the Games’ 4000 metres individual pursuit event. It is further noted that Jonker had assisted his English opponents in the pursuit to similarly streamline their crash hats (2). Unfortunately, the English duo responded by duly eliminating the South African from the pursuit, with one – Norman Sheil – winning gold and the other –Tom Simpson – taking silver in the event.

But it is clear from the SC article that the Jonker–Hettema innovation was not entirely original for, as it observes with quaint hyperbole:‘quite a few of the spectators at Maindy were a little shaken at seeing the Hettema–Jonker style in streamline headwear. It was the first time I had seen a “Rivière” pattern plastic–covered crash hat…’

The allusion here is to the French rider, Roger Rivière, who had successfully broken his own hour record on Milan’s Vigorelli track in 1958. As the French journalist Pierre Chany reported, Rivière rode ‘…wearing a helmet covered in nylon, varnished shoes and a world championship jersey made of silk’. At the time, Rivière was the reigning world 5000 metres professional pursuit champion, a title he had held since 1956. In 1957 he had set the hour record at 46.923 Km. also at the Vigorelli, beating the previous record held by Italian Ercole Baldini (46.394 Km set in 1956). In 1958, using his aero apparel, he increased this to 47.431 Km. The widespread publicity accorded Rivière’s achievement in the cycling press of the day was undoubtedly what inspired the South African duo to emulate his aero–headgear at the Commonwealth Games. However, there is no evidence to suggest that the Rivière/Jonker–Hettema aero crash hat innovation caught on subsequently (3). For instance, photographic images from the 1970s of the likes of Dutchman Roy Schuiten winning the world pursuit championship and of Eddy Merckx setting his hour record show them as wearing conventional unmodified ‘Danish’–type crash hats.

However, if these 1950s aero–innovations had little lasting impact, developments some twenty years earlier in the 1930s certainly did, albeit in a direction which was ultimately to place them outside the mainstream of competitive cycling. The early 1930s saw the introduction of both recumbent and ‘streamlined upright’ machines in an attempt to break the hour record which had been on the shelf for nearly twenty years. It had been set at 44.247 Km. in 1914 by the Swiss cyclist with the unforgettable name of Oscar Egg (4). In 1933, Egg’s longstanding record was broken three times by a trio of French riders: Maurice Richard achieved 44.777 Km; Frances Faure, 45.055 Km; and Marcel Berthet a stunning 49.992 Km. But whereas Richard rode a conventional period track machine, Faure used an ‘open’ (unfaired) recumbent and Berthet a ‘streamlined upright’ (5).

The UCI immediately stepped in and officially banned both of these two types of aerodynamic machine from competition in 1934. The UCI was, of course, to do this once again in the year 2000, banning the aerodynamic hour record–breaking machines of the 1990s used by Graeme Obree and Chris Boardman to set new marks (6). They even retrospectively disallowed Moser’s 1984 hour record on the same grounds and reinstated Merckx’s 1972 hour record of 49.431 Km as the benchmark on the grounds that he used a conventional track machine. The current UCI record, set on a ‘conventional machine’ in 2005 by Ondrej Sosenka, is 49.700 Km. But recumbent and upright streamlined machines, while long consigned to the competitive wilderness by the UCI, have nevertheless continued under the auspices of the IHPV (International Human Powered Vehicle Association).

Thus, while it is obvious that the aero–consciousness exhibited by the South African trackmen Abe Jonker and Jan Hettema at the 1958 Commonwealth Games represents but a footnote to the history of aerodynamics in cycle sport, it nevertheless draws attention to a seemingly recurrent theme in competitive cycling and raises further questions about it. For instance, it leaves me wondering whether aerodynamic innovations large and small, successful and otherwise, haven’t always been a feature of cycle sport?

Footnotes:

1) Laurent Fignon was nicknamed ‘Le Professeur’ in France because of his studious appearance and manner. His palmares included the Tour de France in 1983 and 1984, the 1989 Giro d’Italia and the Milan–San Remo classic in 1988 and 1989. He died of cancer on 31 August, 2010, aged 50, having followed the 2010 Tour.

2) Abe Jonker and Jan Hettema were two of South Africa’s leading track cyclists in the late 1950s at a time when track cycling was at its most popular in the country. Jonker was the national 4000 metres individual pursuit champion in four successive years, 1957–1960. Hettema was more of an allrounder, winning the national 5 mile championship in 1957 and competing in the 1000metre time trial in the 1958 Commonwealth Games in which he finished 7th. After retiring from cycling, Hettema became a leading local car rally driver.

3) Sadly, Rivière’s own subsequent cycling career was terminated prematurely by a horrendous crash on a mountain descent in the 1960 Tour de France in which he broke several vertebrae in his back. He never raced again and spent the rest of his life confined to a wheelchair. Rivière is reported to have subsequently confessed to using performance–enhancing drugs during his cycling career. His 1960 Tour crash was originally attributed to brake failure which was blamed on his team mechanic. Subsequently, it was suggested that it was due to Rivière’s reflexes being drug–impaired. He died of throat cancer in 1976, aged 40.

4) Oscar Egg (1890–1961) was one of the most colourful figures of cycle sport in the first half of the 20th century. After a long and successful cycling career on both road and track which included winning stages in the Tour de France and many Six Days (including several in the US) he established a successful cycle business based in Paris. He is remembered for creating the ‘Osgear’ which was widely used by cyclists before World War II and for his stylish Oscar Egg ‘Super Champion’ lugs used in building classic racing frames.

5) Berthet and Egg had been rivals for the hour record during the belle époque before World War I, with Egg finally emerging triumphant immediately before the war. During the 1930s, Egg was instrumental in developing various streamlined machines which attracted much attention at the time and even contemplated using one himself to regain the hour record.

6) During the 1990s there was intense rivalry between the Scotsman Graeme Obree and the Englishman Chris Boardman in British 25 mile road time trials, track pursuits and ultimately the World Hour Record. Both exhibited extreme aero–consciousness. Obree, who acquired the image of being something of an eccentric, designed and built a machine himself which gave him a ‘praying mantis’ position with his arms tucked into his chest. In 1993 he used this to establish an hour record of 51.596 Km, beating Moser’s 1984 record. A few days later Boardman, who in association with the Lotus racing car organisation developed an aerodynamic machine, beat Obree with a distance of 52.270 Km. In 1994, Obree regained the record, setting it at 52.713 Km. The UCI stepped in with various ad hoc disqualifications regarding the machines being used. Obree responded by developing an extended ‘Superman’ position.

Simultaneously, top continental cyclists of the day attempted the hour record using various aerodynamic machines, with first Miguel Indurain and then Tony Rominger both beating Obree’s 1994 mark. Finally, in 1996, Boardman set the record at 56.375 Km. In 2000, however, after the UCI had banned all aero machines, Boardman set an hour record for ‘conventional’ machines of 49.441 Km which was 10 metres further than Merckx’s 1972 record. Through the inconsistent and ad hoc decisions it has made with regard to aerodynamics down the years, the UCI has created the strong suspicion in some circles that it regards the hour record as a prestigious ‘blue riband’ award reserved for established leading cyclists rather than being open to aerodynamically sophisticated arrivistes.

REFERENCES

Books

Abt, S. (1990). Greg LeMond: The Incredible Comeback. London: Stanley Paul.

Jowett, W.A. (1981). Centenary: 100 Years of Organised South African Cycle Racing. South Africa: SACF.

Obree, G. (2004). Flying Scotsman: The Graeme Obree Story. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Van den Plas, R. (1988; 3rd edition). The Bicycle Racing Guide. San Francisco: Bicycle Books.

Watson, R. and M. Gray. (1978). The Penguin Book of the Bicycle. London: Allen Lane/Penguin.

Websites

In addition to www.classiclightweights.co.uk a Google search was undertaken for the following:

- Cycling Hour Record

- Francesco Moser

- Laurent Fignon

- Oscar Egg

- Roger Rivière.

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.