Sculptured in Steel: The three historic lightweight frame designs and beyond

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

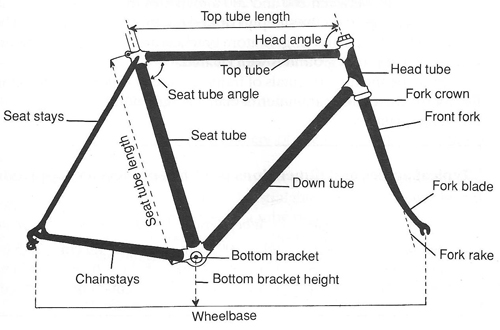

The frame is the fulcrum of the lightweight bicycle, making its design critical to the machine’s overall performance.

It may be thought that the diamond frame design of the ‘safety’ bicycle has remained essentially the same ever since its invention in the 1880s. But in the period of roughly a century following its inception, the steel frame as developed for sporting purposes changed subtly yet significantly. There was a succession of three different diamond frame design templates. These were generic patterns widely adopted by the leading frame builders of their day. To the practised eye, they serve to precisely ‘date’ any specific lightweight frame to a particular period.

Rather than simply reflecting irrational fads and fashions amongst generations of sporting cyclists, each of these templates represented the frame design best suited to the cycling conditions and competitions prevailing at the time. These three can be designated:

- The Original (c.1890 -1910)

- The Continental (c.1910 -1930s)

- The International (c.1935 -1980s)

Inevitably there were overlaps, with some frame builders and enthusiasts remaining doggedly faithful to the established design. Despite such loyalty, in each case the older pattern was ultimately eclipsed by the new.

In the late 20th century new superlight materials – aluminium, titanium and carbon fibre – began to replace steel tubing in lightweight frame construction. In the process, a new frame template emerged, superseding the International design. This combination of novel materials and new template justifies the dominant early 21st century form of the lightweight diamond frame being termed the ‘Postmodern’.

In what follows the leading characteristics of each of these lightweight diamond frame types are related to its specific historical context.

The Original steel frame (c.1890 – 1910)

The provenance of the Original frame type can be traced to Starley’s Rover ‘safety’ machine of the 1880s. It was a design rapidly adopted by contemporary constructors of bicycles throughout the industrialised world. In cycle sport, the high-wheeled ‘Ordinary’ was quickly superseded by the ‘safety’ machine in the late 19th century.

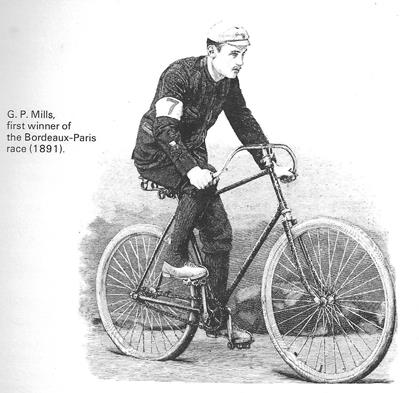

Period images of cycling champions on their safety bicycles, like that of G.P. Mills, reveal the distinguishing features of the Original frame type: sloping top tube, long wheelbase, lengthy head tube, relaxed head and seat tube angles (±66°). The rider’s main bodyweight was located firmly over the rear of the machine, thus maximising drive wheel traction. The long wheel base made for stability, the slack frame angles facilitated shock absorption as did the raked fork blades. The relaxed head angle also increased the self-centring tendency (castor effect) of the front forks. This in turn necessitated the use of wide handlebars to manoeuvre the machine.

These leading features of the Original frame template combined to effectively meet the rigorous demands made on both riders and machines by the rough unmade roads of that time. In short, It was a frame design entirely appropriate to the circumstances of its use.

The Continental frame template (c.1905 – 1935)

Cycle sport flourished in Continental Europe on the cusp of the 20th century, particularly in France. On the road, this period saw the establishment of many of the one-day classics like the Bordeaux-Paris. Multi-stage races followed, starting with the Tour de France in 1903. From the outset all these road races were en ligne mass start events.

In addition, in this era numerous velodromes were constructed, including Paris’ indoor Vel d’Hiv. On the steeply banked European tracks the introduction of motorcycle pacing machines into the then hugely popular long distance ‘stayer’/demi-fond event led to average race speeds of between 60 and 80kph being achieved on massive gears of 120″-140″.

Not surprisingly in response to this diversification in cycle sport, innovative frame builders on the Continent soon developed new lightweight frame designs.

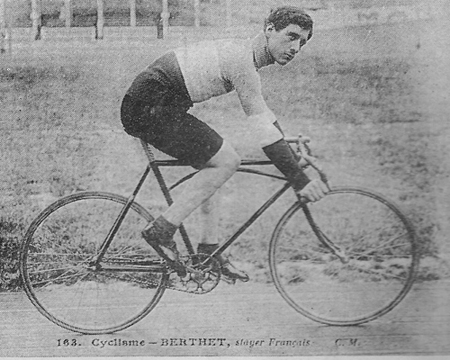

Images of the competitors in early Tours de France from 1903 onwards show them riding machines with a frame profile which was significantly different from the Original. The design of this new ‘Continental’ frame was minimalist and the machines weight conscious. The Continental frame accommodated smaller 26″ wheels with laminated wooden rims rather than the heavy 28″ steel rims of the Original. In addition, the Continental frame type was brazed throughout whereas on the Original the seat stays and sometimes also the chain stays were bolted to the main triangle.

While the head and seat angles remained relatively relaxed (±68°), the new frame type was more compact than its predecessor, differing also in having a horizontal top tube. The saddle was consequently set higher and the handlebars lower, giving the rider a more aggressive forward position on the machine. This in turn placed the rider’s weight more on the handlebars than was the case on the Original.

Similarly, the state-of-the-art track machines of the period exemplified the Continental frame template.

But while the new lightweight frame pattern was widely adopted on the Continent in the early 20th century before WWI, in Britain bicycle design and production remained faithful to the Original template. As a result, when an example of the new type of Continental road machine was first exhibited at a cycle show at London’s Olympia in 1913 it created a sensation.

This new lightweight on display had been constructed by E. Bastide of Paris. At the time Bastide was a leading specialist French lightweight frame builder noted also for producing demi-fond machines for track racing. The Bastide road machine was shown on the stand of the London-based Constrictor Tyre Company which had recently been joined by Leon Meredith. Meredith was a multiple amateur demi-fond world champion, winning the world title no fewer than seven times between 1904 and 1913. Unlike his insular British contemporaries, Meredith regularly travelled to compete on the Continent and was thus exposed to the latest advances in racing technology and machine design abroad.

The cosmopolitan Leon Meredith must therefore ultimately be credited with having introduced the revolutionary new design into Britain. This was on the eve of WWI. Although there is evidence of some British lightweight builders as having adopted it during the war years, its rapid spread in British cycling circles was deferred until the 1920s. It was during this decade that the Continental frame template was popularised in Britain by specialist frame builders such as Granby, Maclean, Saxon, F.W. Evans, Grubb and Selbach.

The Continental design was supported by influential British cycling writers of the time writing under the pseudonyms of ‘Wayfarer’ (W.M. Robinson) and ‘Kuklos’ (Fitzwater Wray). They championed an ascetic, fresh-air way of life in the great outdoors with which the minimalist Continental lightweight design accorded perfectly. It was an ethos captured in the idyllic cycling art of Frank Patterson, whose quiet rural scenes invariably featured cyclists with Continental-style machines.

The Continental frame type was inherently more rigid than its predecessor. This derived from its compact triangulation and its being of brazed construction throughout.

The road systems and surfaces of much of mainland Europe suffered serious damage during WWI. In the 1920s these remained generally poor and underdeveloped. Thus the Continental lightweight frame template, while of pre-war origin, continued to be eminently suited to the needs of sporting cyclists in mainland Europe during this decade. It matched the prevailing cycling conditions of the time. Indications are that public roads in Britain were also slow to improve in the post-war period, favouring the Continental frame design.

The International frame design (c.1935 – 1980)

In the early 1930s a few leading specialist lightweight frame builders began to offer customers a choice of either a ‘conventional’ (Continental) or a more upright frame design. This signalled the arrival of the ‘International’ lightweight frame template.

The hallmarks of the new International style, clearly distinguishing it from its two predecessors, were significantly steeper head and seat angles (70°-72°) and markedly shorter wheelbases (40″- 42″). This new generic design coincided with a number of novel developments at this time. These included:

- The construction of new superfast wood surfaced tracks: Milan’s Vigorelli built in 1935, 397m per lap with 42°bankings and the similar 1936 Berlin Olympics velodrome, both designed by the noted German track architect, Clemens Schürmann (1888-1957).

- Major improvements in road systems and road surfaces linked to significant increases in motor vehicle traffic.

- The shortening of the length of stages in races like the Tour de France from an average of 400km before WWI to 200km in the 1930s, leading to a greater emphasis on speed rather than simply endurance.

- The first appearance of the lighter Reynolds 531 steel tubing in 1935, succeeding the heavier gauge Reynolds HM tubing.

- The general acceptance of the derailleur multiple-gear freewheel system in European road racing.

- The 1930s boom in Britain of fixed-distance road time trialling, including the BBAR competition, with riders seeking fast times using minimalist short wheelbase fixed wheel ‘Road/Path’ machines.

- The widespread commercial promotion of track racing, including six-day events in both Europe and the USA, as a spectator sport on purpose-built banked velodromes with smooth cement or wood surfaces.

- Increased international contacts and competitions between previously distinct cycling traditions and technologies, accelerating the spread of innovative designs.

In Britain, a new generation of lightweight builders emerged in the 1930s who strongly promoted the International frame template. Claud Butler was a leading figure in this movement, producing models like the ‘DSH Path’ which followed the new International design. The flamboyant Butler discreetly sponsored star amateur international trackmen of the day like Dennis Horn, Toni Merkens, Bill Maxfield and later Reg Harris to publicise his innovative machines. They in turn shared their knowledge gained from racing on Europe’s steeply banked velodromes with their British frame builders.

The International frame template in post-WWII cycle sport

The revival of cycle sport after WWII gave new impetus to the International design. The road machines, with derailleur gears now standard, ridden by new post-war stars like Coppi and Koblet exemplified the International frame template. In the 1940s, the modernising BLRC’s (British League of Racing Cyclists) promotion of mass start road racing in Britain stimulated the wider adoption of the International frame template in the UK. British lightweight frame builders of the 1940s and 1950s began to give their models exotic names like ‘Vigorelli’, ‘Italia’ and ‘Continental’. The ‘gold standard’ steel road racing frame of the era quickly became one with parallel 72° head and seat angles and a 40″ (101.6cm) wheelbase accommodating 700C (27″) wheels.

The International template was similarly the basis of track machine design in this period. This is revealed by the dimensions of the Reg Harris Raleigh machine with its 74° parallel head and seat angles and a 40″ wheelbase.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the International steel lightweight frame design had established itself as the dominant template worldwide. Reynolds 531 steel tubing was preferred by lightweight frame builders in Britain and France (Bertin, Geminiani, Gitane, Helyett, Lejeune, Liberia, Louison Bobet, Mercier, Motobecane, Peugeot, Stella, Urago) together with Nervex ‘Professional’ lugs.

However, by the mid-1960s Italian frame builders had emerged as the supreme exponents of the International style, constructing state-of-the-art frames with steeper angles (73°-76°) and shorter wheelbases (98-100cm/38.5″-39.5″) than ever before . Together they formed a veritable A to Z of specialist steel lightweight builders, each with distinctive flourishes. The most notable amongst them were:

Atala, Battaglin, Benotto, Bianchi, Bottecchia, Carrera, Chiorda, Cinelli, Ciöcc, Colnago, Colner, Daccordi, De Rosa, Freschi, Gios, Guerciotti, Masi, Olmo, Paletti, Pinarello, Pogliaghi, Rossin, Scapin, Tommasini, Viner, Wilier, Zullo.

Columbus steel tubing was the material of choice of these Italian master frame builders, together with Cinelli investment cast bottom bracket shells and fork crowns. The dominance of British Reynolds steel tubing was thus seriously challenged. Reynolds responded by developing the superlight 753 frame tube, with tube walls measuring as little as 0.3mm.

The specialist Raleigh Ilkeston lightweight development section, established in 1974, constructed the legendary Raleigh 753 lightweight frames in the International style. These frames were ridden by the all-conquering TI-Raleigh pro road team of the day led by Dutch stars like Zoetemelk, Kuiper, Raas and Knetteman and the German, Dietrich Thurau. Reynolds 753 tubing was rendered exclusive by its availability being restricted to frame builders who had passed a stringent test instituted by Tube Investments (TI).

The specialist Raleigh Ilkeston lightweight development section, established in 1974, constructed the legendary Raleigh 753 lightweight frames in the International style. These frames were ridden by the all-conquering TI-Raleigh pro road team of the day led by Dutch stars like Zoetemelk, Kuiper, Raas and Knetteman and the German, Dietrich Thurau. Reynolds 753 tubing was rendered exclusive by its availability being restricted to frame builders who had passed a stringent test instituted by Tube Investments (TI).

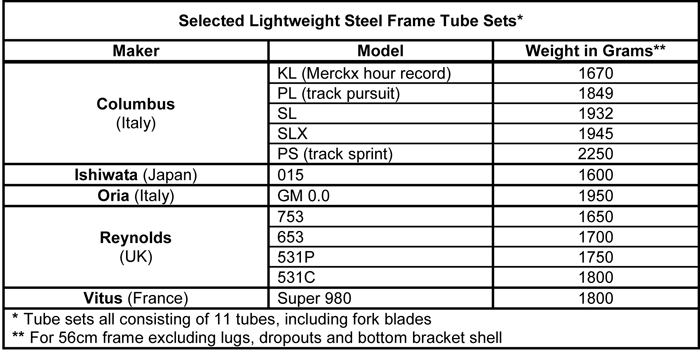

But other steel tubing producers also emerged, creating tubes eminently suited to the construction of lightweight steel frames. Japanese Ishiwata and Tange lightweight steel tubing was favoured by some frame builders, French Vitus tubing by others and Italian Oria by others again.

Over time, a variety of steel frame tubing types and tube profiles, including early ‘aero’ shapes, were introduced. Cost and availability varied considerably and different frame builders favoured certain tubing types over others. Colnago, for instance, built many road frames in Columbus SLX and introduced special ‘Gilco’ clover leaf profiled tubes as well as the ‘Precisa’ straight-bladed forks. The following table provides further details of various tube sets produced by selected lightweight tubing manufacturers.

New materials and the rise of the Postmodern lightweight frame template

Several unsuccessful attempts had been made down the years to build lightweight frames using either aluminium or titanium tubing. Both materials are inherently lighter than steel but present unique technical challenges in the frame construction process.

Finally, in the late 1970s a breakthrough was achieved in building sufficiently rigid lightweight frames in aluminium while still adhering to the International frame template. These were made by ALAN in Italy and Vitus in France. Frame tubes were joined using adhesives and threaded lugs and tubes. In the US, Cannondale succeeded in producing a lugless frame with the more rigid large diameter aluminium tubes being TIG-welded. Then ALAN and Vitus as well as TVT and Look began producing frames with carbon fibre tubes joined through alloy lugs. Others succeeded in creating lightweight frames in titanium. Frames combining a mixture of aluminium and carbon tubes or titanium and carbon tubes followed. Many of the smaller steel lightweight frame builders were either unable or unwilling to adapt to the new materials and modes of manufacture.

The hegemony of specialist European lightweight steel frame builders was increasingly challenged from the late 1980s onwards by large scale producers in the Far East. They were adept at working in aluminium and carbon fibre.

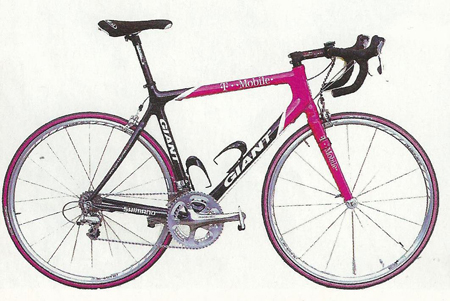

In the process, a new Postmodern lightweight frame design emerged in the mid 1990s. This was a compact frame with a sloping top tube, necessitating the use of a long seat pillar. Initially produced in aluminium in Taiwan by the Giant cycle company, their compact TCR frame design was popularised in European pro road racing circles through being ridden successfully by the powerful ONCE, T-Mobile and Rabobank teams. In 1999 the UCI introduced a rule limiting the drop on sloping top tubes to no more than 8cm over their length.

Inevitably the new Postmodern compact lightweight design was translated into carbon fibre. The early 21st century saw the Postmodern frame template mutate into the carbon fibre monocoque and become the dominant competitive lightweight frame design worldwide.

The age of steel in lightweight frame design

In terms of frame design, G.P. Mills won the inaugural Bordeaux-Paris in 1891 on an ‘Original’, Maurice Garin the first Tour de France in 1903 on a ‘Continental’ and Hugo Koblet the 1951 Tour on an ‘International’. Ultimately, what united these three and their contemporaries is that – unlike their current counterparts – they were all ‘men of steel’.

Sources

The following specific sources were used in compiling this article:

Beneke, M., G. Beneke, T. Noakes and M. Reynolds (1989) The Lore of Cycling. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

Clifford, P. (1965) The Tour de France. London: Stanley Paul.

Fotheringham, W. (2010) Cyclopedia: It’s all about the bike. London: Yellow Jersey Press.

L’Equipe (2003) The Official Tour de France Centennial: 1903-2003. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

Shaw, R.C. (1952) Teach Yourself Cycling. London: English Universities Press.

Shaw, R.C. (ed.) (1975) The Raleigh Book of Cycling. London: Peter Davies.

Theohari, G. (2007) The Cyclist’s Companion. London: Think Books.

Watson, R. and M. Gray (1978) The Penguin Book of the Bicycle. London: Allen Lane.

www.classiclightweights.co.uk See: ‘Classic Designs’, ‘Readers Bikes’ and ‘Lightweight Extras’.

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.