Faded Glory: the demise of leading types of competitive cycle sport

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

Modern cyclists who browse through images of old cycling events will be struck by how dated many of them appear. It is not simply the modes of dress of the riders and spectators and the period racing machines that have this effect but often the very nature of the events themselves. Many types of races have disappeared completely from the modern cycling scene, some have massively declined in both popularity and prestige while others have been reinvented in barely recognisable new forms.

Viewing these old cycling images today and seeing the proud stances of the victors coupled with the admiring glances of the surrounding fans induces a bittersweet feeling. Who were these people enjoying the fleeting glory of the moment and what exactly were these events in which they had triumphed? This article seeks to explore this question further.

The origins of modern competitive cycle sport: a brief history

Competitive cycling – ‘bike racing’ in modern parlance – dates from the invention of the high wheeled ‘Ordinary’ in the 1860s and continued to gather momentum following the emergence of the ‘Safety’ bicycle in the 1880s. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, its popularity spread rapidly throughout the urban-industrial countries of Europe (including, centrally, the British Isles) and North America and thence to the European settler colonies in Africa and Australasia.

Initially, there was little standardisation in the types of events competed in by cyclists in different parts of the world. Gradually, however, definite patterns began to emerge. Oval cycling tracks were built and improvements were made to the public roads and ‘road’ and ‘track’ cycling became the two established variants of the sport. Some fundamental national differences, such as British road ‘time trialling’, were to persist through to the present. However, as international events involving multinational fields of star riders proliferated under the impetus of both sponsorship by bicycle manufacturers like Britain’s ‘Raleigh’ and enterprising promoters like the Englishman Henry Sturmey, increasing standardisation of the sport occurred at this new elite level. This in turn had a trickle-down effect, as rapidly increasing numbers of riders keenly sought to ascend the emergent hierarchy of those types of events which were acquiring the most status and prestige.

A major step towards international elite event standardisation occurred with the formation of the International Cycling Association (ICA) in 1892. The ICA introduced the first annual ‘official’ World Championships in 1893 which were held in Chicago and included only three track events, all reserved exclusively for amateurs. These were a short distance ‘sprint’ race and a middle distance event, both won by the American A.A. ‘Zimmy’ Zimmerman. He went on to become the first international cycling superstar and was sponsored by Raleigh Cycles. The third was a long distance human paced endurance ‘stayers’ event won by Laurens Meintjies of South Africa.

The ICA continued to organise its annual World Championships in both America and Europe, including professional titles from 1895 onwards. However, the ICA remained troubled by internal disputes between different national representatives. Much of this centred on a dispute over the varying definitions of ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ cyclists. Matters were further complicated by the advent of the Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 which insisted upon the ‘strict amateurism’ principles of the cycling associations of the British Isles. The issue finally came to a head in 1900, when many leading cycling nations seceded from the ICA and formed the ‘Union Cycliste International’ (UCI). In so doing, the strictly amateur British cycling associations and their allies, who together had dominated the ICA, were isolated and the organisation rapidly collapsed. From the outset of the 20th century, therefore, the epicentre of international cycling bureaucratic power shifted to the Continent and the UCI.

What happened in cycle sport during the 20th century? More particularly, which forms of competitive cycling dramatically declined over this period? It is with this latter question that the remainder of this article is concerned.

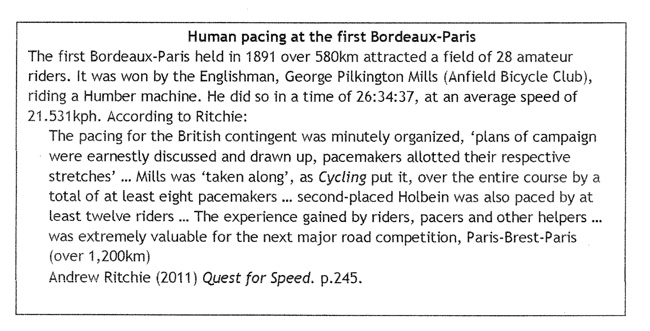

The first victim: human-paced cycle sport

With the advent of the pneumatic tyre equipped Safety machine in the late 1800s, the Ordinary was rapidly totally eclipsed as a racing machine on both road and track. Instead, long distance endurance Safety bicycle events on road and track became fashionable. In both these formats, the competitors raced one another using teams of human pacers to keep themselves in contention for victory. On the road, in long distance events like the 580km Bordeaux-Paris first held in 1891, the riders relied on teams of pacers on solo machines. Individual pacers were replaced at regular intervals to lead their star riders over the course. On the track, pacers rode a variety of machines: solos, tandems, triplets, ‘quads’ and even ‘quints’. In many instances, the pacing teams were funded by sponsors like Dunlop.

However, experiments were soon being made using motorised forms of pacing. In 1897 the Bordeaux-Paris winner, Gaston Rivierre of France, was paced by a motor car at a record race speed of nearly 29kph and thereafter various pacing options were explored.

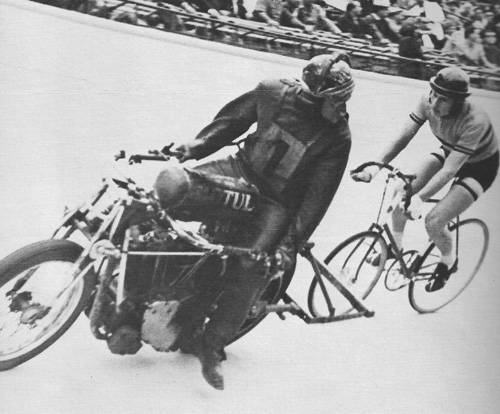

In long distance paced track events, motor cycles were used increasingly. Speeds rose dramatically and, with UCI world paced Stayer (demi fond) titles on the track for amateurs and professionals being contested annually, this became an established prestige track event. Motor pace riders turned massive gears of between 120 and 140 inches. The great British rider, Leon Meredith, won the UCI amateur world paced Stayer title seven times between 1903 and 1913 to become an international star:

Such races were a dramatic new departure in a modern, machine age. They were noisy, smelly and extremely dangerous events held within the confines of a banked, cement velodrome with eager spectators surrounding the action. Speeds as high as 100kph, and the participants’ willingness to take the consequent risks involved characterised this new discipline … and these ‘stayer’ races became hugely popular in France, Germany and the United States before the First World War, the element of danger adding drama to the sport. The enormous sums of money earned by the leading professionals … ensured a constant stream of new talent prepared to accept these risks.

Andrew Ritchie (2011) Quest for Speed. p.341.

According to Ritchie, one source estimates that between 1899 and 1928, 33 riders and 14 pacemakers were killed on European and American tracks. In Berlin in 1909, a motor pacing machine left the track resulting in nine deaths and 50 injuries amongst spectators.

On the track, human paced stayer events were increasingly overshadowed by the motorcycle paced events. Nevertheless, that human paced long distance track events lingered on into the early part of the 20th century in some countries is revealed by Jowett’s report on South African cyclists who raced in Britain: In 1913 W.R. Smith competed in England and won the 100 miles Tandem Paced Championship of England, as well as breaking the existing record for the distance … Prior to competing in the (1920) Olympic Games in Antwerp, three of the cyclists took part in the 50 miles British Tandem Paced Championships at the famous Herne Hill stadium, against champions from all parts of the world. Kaltenbrun and Walker rode the tandem, pacing W.R. Smith and they won the title, despite the tandem crashing at 20 miles.

Walter Jowett (1983) Centenary: 100 years of organised South African cycle racing. p.56. But the UCI amateur motor paced stayer world title itself was discontinued in 1914 and only revived again in 1958, apparently under pressure from the Eastern Bloc where the event had remained popular. In 1958, the UCI amateur motor paced world title was duly won by the East German rider, Lothar Meister.

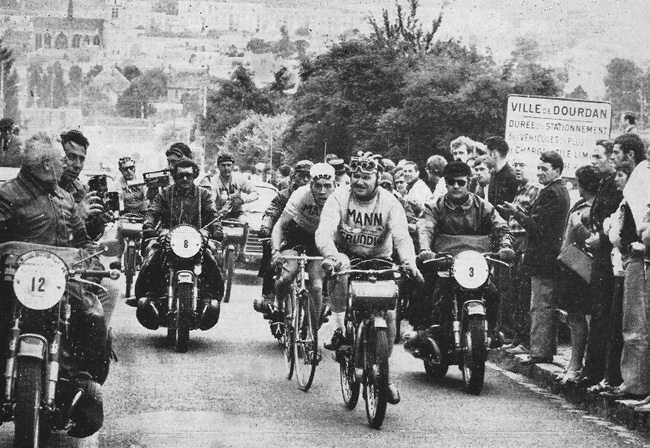

On the road, human paced long distance races declined even more rapidly, with the Bordeaux-Paris being one of the few to retain it for a time in various forms. To quote Peter Clifford: Originally pacing was by teams of single bicycles, but tandems, triplets and even quadruplets were soon introduced. After a few years when cars were used for part of the race, bicycles were re-introduced and held their own until the advent of motor-bikes in 1931. The Derny, a type of moped, was first used in 1938, and has been used ever since, only the town from which pace is taken having varied. Peter Clifford (1973) Cycling Classics, 1970-72. P.63.

By the 1970s, that it remained a paced long distance road event made the Bordeaux-Paris a quaint survival from the past. Apart from it and the likes of the Criterium des As (an exhibition race behind derny motorcycles by a selection of elite pros such as Merckx on a short circuit in central Paris), road cycle sport in Continental Europe had assumed an exclusively ‘massed-start’ en ligne form. The last Bordeaux-Paris was held in 1988, after which it disappeared completely from the professional cycling calendar.

In the early 1990s, the UCI terminated the world motor paced title. Thus both human and motor paced cycle sport on road and track had to all intents and purposes ended by the end of the 20th century. Its ghost survives today as elements of some winter six day races, while the derny pacing motorcycle features in Keirin track events at UCI world contests and at the Olympic Games.

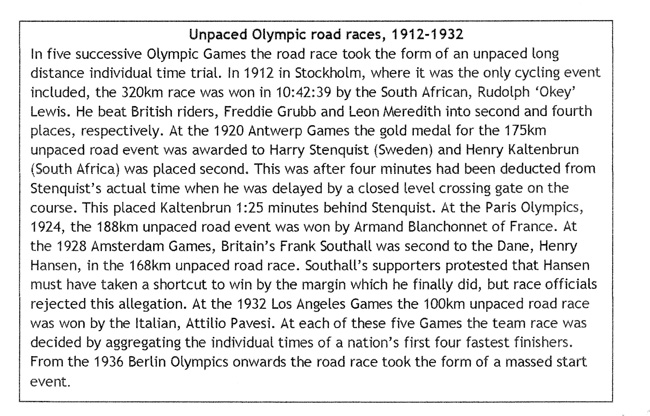

Unpaced cycle sport: varieties and vicissitudes

Like paced racing, unpaced racing involving usually individual riders or in some instances small teams, dates from the 19th century origins of the sport. On both track and road and in many different guises, it consists of riders being either timed over specified distances or their distances travelled within particular time frames being measured. The ‘Hour Record’ is an example of the latter type of event, as are 12-Hour and 24-Hour events. The British 25-mile unpaced race and the modern Olympic road ‘time trial’ exemplify the former type. As with paced racing, the standardisation of unpaced events evolved over time, assuming a variety of forms in different countries and at international level.

Unpaced events – ‘time trials’ –are indelibly associated with cycle sport as it developed in the British Isles during the course of the 20th century. Due to complex historical reasons, for much of the century it remained the only form of road racing to exist there. In Continental Europe, by contrast, the unpaced road event – contre le montre – remained a rarity. It was only in the post-World War II period that unpaced racing on British roads was increasingly challenged by ‘massed start’ events organised by the ‘rebel’ British League of Racing Cyclists (BLRC). Consideration of the byzantine nature of the conflict between the arrivistes of the BLRC and the traditionalists of the National Cycling Union (NCU) and Road Time Trials Council (RTTC) lies beyond the scope of this article. However, it was ultimately largely resolved by the BLRC and NCU uniting to form the British Cycling Federation (BCF) in the late 1900s. As a result, massed-start, Continental-style road racing became firmly established in Britain. Nevertheless, the RTTC remained apart and has continued to successfully control and organise time trials on British roads as ‘Cycling Time Trials’ (CTT) through to the present.

In Britain for much of the first half of the 20th century and into the 1970s, unpaced racing and particularly road time trialling (10, 25, 30, 50 and 100-mile events and 12 and 24-hour races) continued to enjoy the highest prestige. Its leading exponents and national champions – like Frank Southall in the 1930s and Ray Booty in the 1950s – were lauded in the national cycling press and revered by the mass of grassroots cyclists who regularly ‘tested’ themselves in similar events during the summer months. In its heyday, British road time trialling was a secretive sporting cult widely pursued primarily by urban working class people and served by small specialist local frame builders. They produced limited numbers of time trial-specific (‘Path’) lightweight steel machines for local devotees. Today, these individualistic, handcrafted bespoke frames and machines are prized by collectors across the world. Bearing idiosyncratic clues to their provenance, particularly in their elaborate hand cut lugwork, these frames bear the prosaic names of their fabricators like A.S. Gillott, Hetchins, Bill Hurlow and Ephgrave. Together they represent the holy grail to the classic cycling cognoscenti.

From the 1950s onwards, with the advent of the BLRC and massed start road racing, time trial events progressively declined in terms of cachet in British cycling circles. Reports of the exploits of pioneering British road riders abroad like Brian Robinson, Tommy Simpson and Barry Hoban appeared in specialist magazines such as Sporting Cyclist. As a result, the Anglophone cycling community began to worship new gods. These were the Continental road racing professionals such as Bartali, Coppi, Louison Bobet, Charly Gaul, Bahamontes, Jacques Anquetil and the two ‘Belgian Riks’, van Steenbergen and Van Looy. They were the exotic superstar winners of the great European stage races and one day classics in the years following World War II. In the 1960s they were transcended in the cyclists’ pantheon by the Belgian cycling superstar, Eddy Merckx. Today the 20th century stars of British road time trialling are largely forgotten men and women.

Conversely, in European cycle sport, the unpaced road event remained a rarity throughout the 20th century. In some stage races, like the Tour de France and Giro d’Italia, road time trials either for individuals or for teams were erratically included as single stages. For a period, annual elite time trials were organised: in France, the Grand Prix des Nations; in Italy, the two-man Trofeo Baracchi. Both featured the leading riders of their day like Anquetil and Coppi. The 142km French event was first held in 1932, the last in 2004; the Italian race was staged from 1944 until 1991. Both were ultimately eclipsed by the UCI introducing the world individual road time trial championship title in 1994. At the 1960 Rome Olympics, a 100km road time trial for four man teams was introduced and continued on into the 1990s when it was replaced by an individual event.

Overall, therefore, while unpaced events on both road and track have exhibited a resilience not matched by paced events, their variety and not infrequent fundamental changes at elite levels of the sport make it difficult to anticipate their future directions.

On the track, unpaced events of many different types developed down the years. The world ‘Hour Record’ proved to be the most enduring of these. Its first holder was Henri Desgrange, who went on to found the Tour de France in 1903. In 1893, Desgrange – riding alone and unaided – covered 35.325 kilometres in one hour on Paris’ Buffalo outdoor velodrome. Since then the world hour record has continued to be pursued, albeit somewhat erratically, down the decades. Many of the sport’s established superstars like Coppi, Anquetil and Merckx have held it at various times. It has thus continued to be considered cycling’s Blue Riband event.

The short distance track individual time trial, standardised to 1,000 metres for men, is one event which survived at Olympic level over the entire 20th century, but has since disappeared from the Olympic schedule. The UCI amateur track 1,000 m individual TT world title was introduced in 1966 when the championships were held in West Germany. Pierre Trentin of France won the first title and it is an event traditionally dominated by powerful track sprinters. The track pursuit race is generally regarded as an unpaced event. Typically held over distances of 3,000, 4,000 or 5,000 metres, in its purest form it involves two individuals or teams starting on opposite sides of the track and ‘pursuing’ each other over the fixed distance.

The winner is the individual or team which crosses the finish line first and thus sets the faster time for the required distance. The track team pursuit first featured in the 1900 Paris Olympics and then at all subsequent Games. In contrast, the individual pursuit for amateur and professional men first appeared at the UCI world championships after World War II, and for women from 1958. Not surprisingly given the time trialling pedigree of British riders, Norman Sheil, Beryl Burton and Hugh Porter all won several world pursuit titles in the period from the 1950s through to the 1970s.

The handicap race on road and track

Two of the most historic Australian cycling events which have long enjoyed the highest esteem in cycle sport in that country were both handicap races: on the track, the ‘Austral Wheel Race’ held annually in Melbourne ever since 1887; on the road, the Melbourne to Warrnambool classic over some 165 miles and held annually since 1895. Neither was run during the two world wars. Both the riders who participated in these events but did not necessarily win and many of the actual winners themselves represent literally an historical ‘who’s who’ of Australia’s track and road cycling elite. They include Sir Hubert Opperman, Russell Mockridge, Sid Patterson and Danny Clark. Clearly these are handicap races which have been held in the highest regard since their earliest days. Substantial prizes in either kind or cash were on offer. Many of the winners have been ‘middle markers’ who enjoyed advantages over the scratch men. In the road event the rider who set the fastest time over the course was awarded a special prize.

The first Austral Wheel Race was staged over a distance of two miles at the historic Melbourne Cricket Ground. It was subsequently held at various other venues in Melbourne. Riders’ handicaps were established through the holding of a series of qualifying heats. The legendary Australian cyclist, Hubert ‘Oppy’ Opperman finished second in the final of the 1925 event. In 1954, the race was won by the Englishman, Alan Geddes, riding off a handicap mark of 130 yards. Among the rare scratch riders to win the event were Sid Patterson in 1962 and 1964 and Danny Clark in 1977 and 1986. The classic Warrnambool handicap road race had small bunches of riders starting at intervals, with the scratch group being the last to depart. On numerous occasions it was run in reverse, finishing in Melbourne. Russell Mockridge set the fastest time for the race in both 1956 and 1957, but was not first to cross the finish line. In 1980, the great British cyclist, Beryl Burton finished the event to become the first woman to do so. In the mid 1990s, both races finally abandoned the handicap system and the distances were measured in metres and kilometres rather than in the original imperial yards and miles. It was the end of an era.

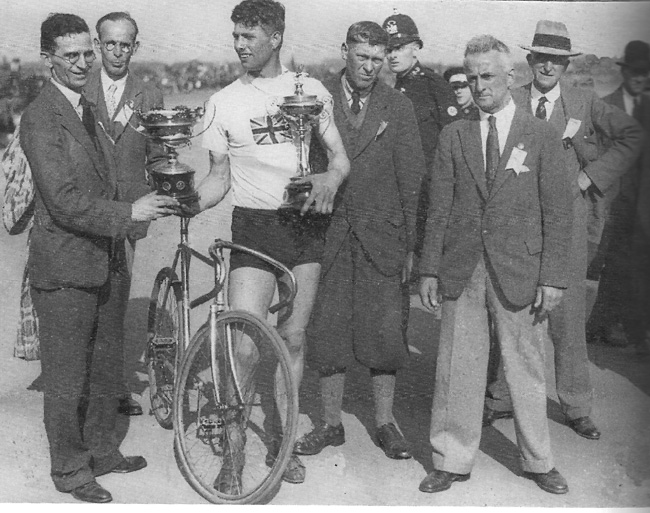

South Africa was another British Commonwealth country in which handicap racing on track and road was popular in the periods on either side of WWII. George Estman, of the Troyeville CC in Johannesburg, was a giant of a man who became a skilled exponent of handicap racing on road and track at this time. A real allrounder, he participated in the 1948 London Olympic road race and won a silver medal in the team pursuit at the 1952 Helsinki Games when the South African squad finished second to the Italian team. Estman had initially entered competitive cycling as a teenager in the 1930s. He first made a name for himself in the sport in 1939 when, as a sixteen year old, he won the prestigious ‘Dunlop 100 Trophy’ handicap road race off a middle marker’s handicap. The ‘Dunlop 100’ was first staged in 1913 by Johannesburg’s elite Rand Roads CC which had the mining magnate, Sir Abe Bailey, as its founding president. After WWI, the race became an established annual classic. Held over a 62 mile (100 km) course from Johannesburg to the Transvaal town of Heidelberg, the winner was awarded the valuable Dunlop silver floating trophy. Today it is an exhibit in the Johannesburg Transport Museum.

Estman was in the forefront of the revival of South African cycle sport after WWII. In 1946 he again entered the prestigious Dunlop 100 handicap, but this time was placed in the scratch group. The race was won on this occasion by middle marker Andrew Fouche who started off a handicap mark of 25 minutes. Nevertheless, Estman set a new record fastest time of 2:43:33 (36 kph) for the event, which was nearly 30 minutes faster than his winning time in 1939. Earlier that same year, he had won the demandingly hilly 104 mile Ladysmith to Pietermaritzburg road race handicap. This event had attracted the country’s leading riders to contest the valuable Speedwell CC trophy. The field of 35 riders was split into A, B, C and D groups and Estman was one of the four scratchmen. These four overhauled all of the other groups and Estman won the finishing sprint in Pietermaritzburg to win in 5:22:40 (31 kph). This beat the previous race record time by 38 minutes. In a remarkably varied cycling career extending into the early 1950s, he also won the national 100 mile unpaced road individual time trial title and both the national match sprint and 1,000 metre TT titles on the track.

Enthusiasm in cycling circles for handicap racing began to wane during the 1950s, with these events being increasingly eclipsed in terms of prestige on the road by massed start races and by bunch races on the track. As to why this should have occurred when it did invites speculation: was it due to the novelty of the other events or the absence of national and international honours for handicap events? Whatever the reasons, the abandonment by the two great Australian classics – the Austral and the Warrnambool – of their traditional handicap format in the 1990s would seem to signal the final demise of the handicap race as a prestige event. If handicaps survive anywhere today, it is on the margins of the sport in local track meetings and in the uniquely British tradition of summer grass track racing.

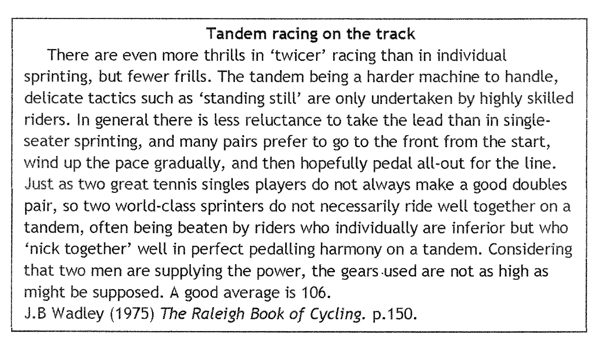

Track and road racing on tandems

As with other the other forms of cycle sport which have already been considered, tandem racing on track and road has a long history. At Olympic level, the track tandem match sprint event over 2,000 metres became firmly established from the 1920 Antwerp Olympics onwards. At the Antwerp Games the tandem sprint gold medal was won by the British pairing of Harry Ryan and Thomas Lance. This event was to feature in all 11 subsequent Olympic Games over a period of some 50 years, ending at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Tandem bicycles and even tandem tricycles figured particularly in the British road time trialling tradition as well as in Road Records Association (RRA) place-to-place timed records. These included the epic 870 mile ‘End-to-End’, Land’s End-John o’Groats record. Given this enduring British interest, it is not surprising that several leading British lightweight builders also produced tandem frames and often also the appropriate accompanying fittings and accessories. Claud Butler, Hobbs of Barbican and Jack Taylor were all noted for manufacturing lightweight tandems for both track and road racing as well as for touring.

In the post-World War II era, one of the first Eastern Bloc successes in international cycling came at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics in the tandem sprint event. At these the Czechoslovakian team of Foucek and Machek won the silver medal while an Australian pairing took the tandem gold. It was the beginning of Eastern Bloc dominance of track tandem sprinting in the latter part of the 20th century.

The UCI introduced a world amateur tandem match sprint title event in 1966 which was to continue on into the early 1990s. Between 1966 and 1988, Eastern Bloc pairings won a total of 14 world tandem sprint titles (Czechs 9; East Germans 3; Poles 2). These nations sourced their track tandems primarily from the two leading Italian bulders, Cinelli and Pogliaghi. Both were based in Milan where they had the fast, elegant Vigorelli velodrome as an ideal place to test their machines crafted in Italian Columbus tandem tubing. Sante Pogliaghi, who worked alone assisted only by a young apprentice, was particularly noted for producing his own heavy duty tandem lugs, bottom bracket shells, fork crowns and front and rear ends.

The paradigm shift which began in track racing at elite level in the mid-1970s involved the sport rapidly abandoning large outdoor tracks in favour of short 250 metre long indoor velodromes. Tandem match sprinting as a premier event became one of the first casualties in the process, dropping off the rosters of both national and international titles. The new small indoor velodromes were totally unsuited to the demands of this type of racing. Today, track tandems feature primarily in some of the events in the burgeoning discipline of paracycling.

Nevertheless, tandems retain a timeless appeal, and not only amongst dedicated cyclists. Tandem events may no longer feature at the apex of the sport internationally, but modern road going tandems remain immensely attractive and popular, figuring prominently in the massive fields of sportives like Cape Town’s annual ‘Argus Tour’ in South Africa.

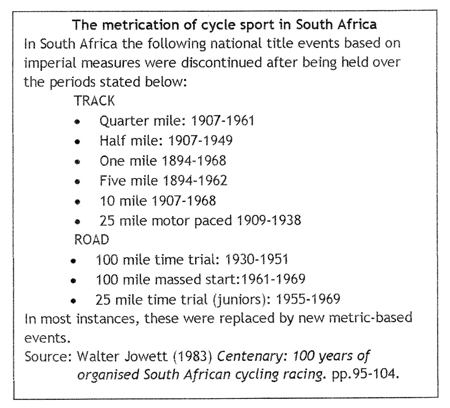

From miles to kilometres: the global metrication of cycle sport

In the 1990s, when the two prestigious Australian events, the ‘Austral’ and the Melbourne-Warrnambool, both abandoned the handicap format, they simultaneously changed from being based on the imperial system of measurement of miles and yards to the metric system of metres and kilometres. In the latter part of the 20th century, this was a transformation which rapidly permeated the sport in many of the Anglophone cycling countries where imperial units of measurement were traditional. In short, globally, the sport rapidly became metricated.

Since its inception, cycle sport in the British Isles, North America, Australasia and the British settler-colonies in Africa had used the imperial system of measurement. On the track, the quarter mile, half mile, one mile, five miles, ten miles and 25 miles were the classic racing distances. It was these events that were contested for national titles, major trophies and entries into the official record books. They were the crème de la crème of track events in these countries. Entire cycling careers were devoted to excelling in them and sporting reputations were built exclusively upon success in these. With the abandonment of the imperial system, many were instantly rendered either obsolete or had their prestige seriously undermined. This was a watershed in the sport in the Anglophone world, dividing old-style cycling from the new, modern form and, in the process, eroding the esteem in which these historic events and their champions were held.

In Britain, the powerful road time trialling tradition entirely rejected metrication. It retained the 10, 25, 30, 50 and 100 mile events as the classic distances together with the 12 and 24 events measured in miles. According to The Cyclist’s Companion (2007, p.27), in 2002 the CTT (the body controlling road time trialling) had 1,000 affiliated cycling clubs, 1,932 road time trials were held in the course of the year and these attracted a total of 85,000 participants. Clearly, the classic British road time trial, while it may have lost some ground in terms of prestige within British cycling circles, has remained a popular national form of the sport. It continues to provide a valuable entrée for newcomers to cycle sport, to afford exponents opportunities to measure their progress ‘against the watch’ and to give those who have retired from active participation to serve as officials, thereby retaining their contact with the sport. In short, it remains a vibrant specialist sporting subculture.

In conclusion

This article has sought to identify the processes of decline of several former leading specific forms of cycle sport: human and motor-paced racing, unpaced racing, handicap racing, tandem competition and events based on imperial measures. If this analysis has revealed anything it is that cycle sport exhibits an almost infinite capacity to retain vestiges of its past while simultaneously renewing itself ad infinitum.

References

Henderson, N.G. (1973) Cycling Classics, 1970-72. London: Pelham Books.

Jowett, W. (1983) Centenary: 100 years of organised South African cycle racing. South Africa: South African Cycling Federation.

Learmont, T. (1990) Cycling in South Africa. Sandton: Media Books.

Ritchie, A. (2011) Quest for Speed: A History of Early Bicycle Racing 1868-1903. El Cerrito, CA: Andrew Ritchie.

Simes, J. (1976) Winning bicycle racing. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Theohari, G. ed. (2007) The Cyclist’s Companion. London: Think Books. p.40.

Underwood, P. (2013) Dennis Horn – Racing for an English Rose. Norwich: Mousehold Press.

Wadley, J.B. ‘Cycle Sport – on the Track’. pp.147-156. In Shaw, R.C. ed. (1975) The Raleigh Book of Cycling. London: Peter Davies.

Watson, R. & M. Gray (1978) The Penguin Book of the Bicycle. London: Allen Lane, Penguin.

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.