Eastern Bloc international competitive cycling in the Cold War

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

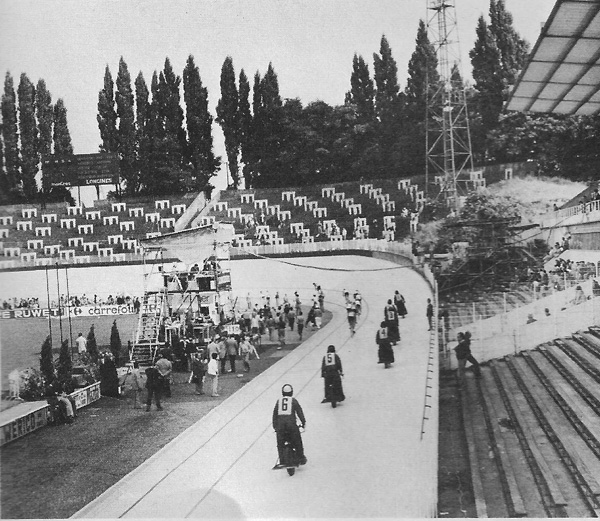

1975 UCI World Championships: Liège, Belgium

The riders, managers, helpers and press who attended the 1975 world cycling championships in Belgium had every right to be critical Poor planning, bad organisation, lack of thought and consideration, utter incompetence and downright carelessness can all be justifiably levelled at the officials in charge. Add to that the awful state of the Rocourt track.

Things did not improve for the road events. Perhaps justice was done in the end, though, as the great cycling nation of Belgium failed to earn a single gold medal during the championships. David Saunders, ‘Championnats du Monde de Cyclisme, Belgique 1975’. International Cycle Sport, No. 89, October 1975, (not paginated).

Despite the Inspector Clouseau-like shambles of the Liège championships, the riders representing several of the state socialist nations of Eastern Europe – Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union – were expected to dominate the scheduled amateur track and road events.

The decade of the 1970s during which these championships were held lay deep in the ‘Cold War’ era. In this ideological conflict sport, including cycle sport, was a major international arena where the two contending world systems – Western capitalism and Eastern Bloc socialism – challenged one another for supremacy. Rejecting professionalism on ideological grounds, the Eastern Bloc espoused amateur sport. In amateur cycling, the events at the Olympic Games and the annual UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale) world championships carried the most international prestige.

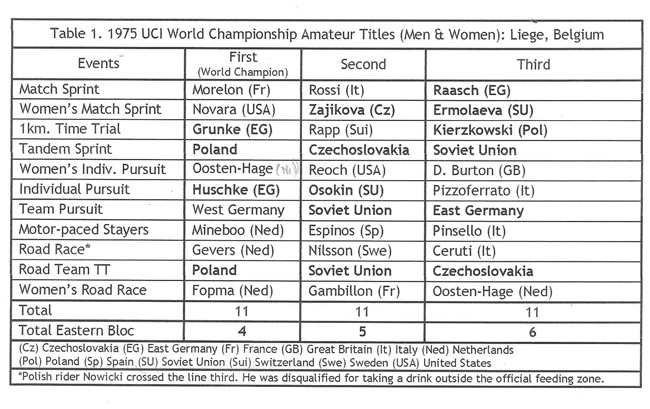

However, the 1975 Liège world championships ended in a stalemate between East and West (see Table 1). Of the eleven amateur titles at stake, Eastern Bloc nations won four, finished second in five and third in three. Overall, of the 33 medals awarded for amateur events at the championships, Eastern Bloc riders won 15 (45%). The Netherlands was the most successful of the Western nations, winning four titles and garnering a total of five amateur medals (15%).

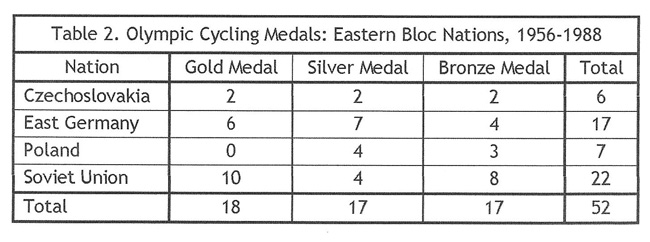

The Cold War and cycle sport

During the Cold War, which originated immediately following World War II and persisted for some forty years up until the collapse of the constituent state socialist regimes in Eastern Europe on the cusp of 1990, Eastern Bloc cyclists participated in seven Olympic Games (excluding the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics which the Eastern Bloc boycotted). In these, starting with Melbourne 1956 and ending with Seoul in 1988, they won a total of 52 Olympic cycling medals (32.7% of a possible 159), including 18 gold medals (see Table 2).

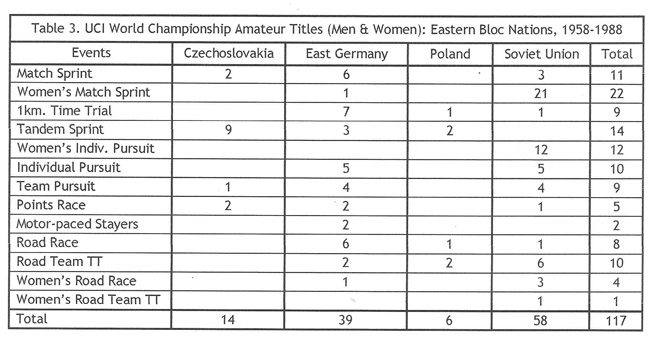

In the annual UCI world championships, Eastern Bloc cyclists won a total of 117 amateur world titles between 1958 and 1988 (see Table 3).

This article charts the rise of Eastern Bloc amateur cycling in the international arena from its beginnings in the 1950s through to its sudden demise in the late 1980s. It does so by focusing on performances at the Olympic Games and the UCI World Championships in particular.

Post-WWII: the emergence of amateur competitive cycling in the Eastern Bloc

In the turmoil of post-World War II Europe, sport became an important element in nation building and social reconstruction. In Western Europe, professional cycling events like the Tour de France and the one-day road classics were soon revived.

In the new post-war ‘Iron Curtain’ socialist states, amateur cycle racing began to figure prominently. The Tour of Poland, first held intermittently before WWII, was reintroduced as an annual event. However, in 1948 it was soon overshadowed by the new ‘Peace Race’ which was sponsored by state-controlled national newspapers. Billed as the ‘Tour de France of the East’, it was an annual stage race contested by the best Eastern Bloc amateurs plus guest teams from the West. Expanding to include stages connecting the capitals of Poland (Warsaw), East Germany (East Berlin) and Czechoslovakia (Prague), it was famously won in 1952 by Ian Steel riding as a ‘Viking’ independent for an invited British BLRC team.

However, Eastern Bloc cycling first fully emerged onto the world stage at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. At these, Czech cyclists won two silver medals in track events. In the 1,000 metre individual time trial, Ladislav FouÄek finished second to the Italian Leandro Faggin with the South African, Jimmy Swift, taking the bronze medal. FouÄek then teamed up with Václav Machek to win silver in the tandem sprint behind the Australians Browne and Marchant. The tandem sprint event was subsequently to become a Czechoslovakian speciality, particularly at world championship level (see Table 3).

Simultaneously, Eastern Bloc cycling apparatchiks began to permeate the hitherto exclusively Western European-dominated UCI corridors of power. In so doing, they came to exert increasing influence on UCI policies and practices. In 1958, four new UCI world amateur titles were introduced: for women, the match sprint, 3,000 metre individual pursuit and road race; for men, the motor-paced stayers’ race which had been discontinued after 1914. The introduction of world titles for women cyclists was a truly revolutionary innovation.

The 1958 UCI world championships proved to be a triumph for both men and women riders from the Eastern Bloc nations. Title winners were:

- Women’s sprint: Galina Ermolaeva (Soviet Union).

- Women’s individual pursuit: Ludmila Kotchetova (Soviet Union).

- Amateur men’s stayer: Lothar Meister (East Germany).

- Amateur men’s road race: Gustav Schur (East Germany).

Galina Ermolaeva was to win a total of six world women’s sprint titles: 1958-1961, 1963 and 1972 in addition to frequently finishing second and third. Gustav Schur repeated his road race victory in 1959 and finished second to his compatriot Bernhardt Ekstein in 1960, sacrificing his own chances to ensure victory by a member of his team.

By the end of the 1950s, therefore, the Eastern Bloc had firmly established itself as a leading force in world amateur cycling.

Eastern Bloc international cycling in the 1960s

Q: What reward are you going to receive for your Olympic gold medal?

A: I’ll be rewarded with the best reward a Soviet athlete can have – the admiration and respect of our nation.

Response by Victor Kapitanov after winning the Olympic road race at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Kapitanov subsequently became the supremo of the Soviet Union’s cycling programme.

At the 1960 Rome Olympics, the Soviet Union’s cyclists garnered five out of the total of 18 cycling medals. In the road race, Viktor Kapitanov mistakenly sprinted for the line on the penultimate lap. Realising his error, he sprinted again on the final lap and beat the host nation’s Livio Trapê into second place. On the track, the Soviet Union won bronze medals in the 1,000 metre individual TT, the tandem sprint and the team pursuit. In the latter event, the East German team won the silver medal, being beaten in the final by the Italian team. Italy also won the new 100km. road team time trial event in which the Soviet Union finished third.

Cycling events for women were not included in the Olympics until the 1980s. However, Eastern Bloc women cyclists continued to dominate the UCI world championships during the 1960s. Russian women, headed by Galina Ermolaeva, won the world sprint title every year throughout the decade. In the women’s individual pursuit, Britain’s Beryl Burton triumphed every year from 1959 to 1963 and then again in 1966, but was succeeded by Russia’s Tamara Garushina and Raisa Obodovskaya in the late 1960s.

Amongst the amateur men at the world championships, East German Georg Stolze won the amateur stayers’ event in 1960, the Soviet Union the team pursuit in 1963, 1964 and 1965 and Omar Phakadze also of the Soviet Union won the match sprint title in 1965.

The number of UCI world title events for amateur men was substantially increased during the 1960s. In 1962 both the 4,000 metre team pursuit and the 1,000 metre individual TT were introduced as well as the 100km road team time trial. All three were already Olympic cycling events as was the tandem match sprint which the UCI introduced in 1966. This brought the total number of amateur UCI titles to be contested annually up to eleven.

This increase in the number of amateur world titles eminently suited Eastern Bloc cycling interests as did the restructuring of the UCI which occurred in 1965. Thereafter, professional cycle sport was administered by the FICP (Fédération Internationale de Cyclisme Professionel) while amateur cycling fell under the FIAC (Fédération Internationale Amateur de Cyclisme) with the UCI remaining as an umbrella organisation. With Eastern Bloc nations dominating the FIAC, the amateur body grew rapidly to ultimately include 127 member nations across five continents.

But while Eastern Bloc cycling successes continued to gather momentum at the UCI world championships during the 1960s, results from the Olympics were disappointing. At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Daler of Czechoslovakia won the individual pursuit title and the Soviet Union took the silver medal in the tandem sprint, but these were the only triumphs. At the 1968 Mexico Olympics, Janusz Kierkowski of Poland won the bronze medal in the 1,000 metre individual TT to give the Eastern Bloc its solitary medal success.

During the 1960s, Eastern Bloc men’s national road teams began to compete successfully in major amateur road races in Western Europe, particularly stage races. Britain’s multi-stage Milk Race and France’s Tour de l’Avenir, both of which were widely reported in the media, were prime targets. In 1962, the Milk Race was won by Eugen Pokorny of the Polish team and in 1966 the Pole, Jozef Gawilezek, triumphed in the race.

Overall, during the 1960s Eastern Bloc cycling consolidated its place as the leading force in international amateur cycle sport.

The 1970s: towards international domination

We were like amateurs against pros. The whole Russian team used to get on the front and not let anyone else in. The only way you could stand a chance was to ride as near as possible to them and wait for them to make a mistake.

Bob Downs. 1970s British Milk Race rider. (Quoted in: W. Fotheringham, 2010. Cyclopedia. p.123)

Eastern Bloc success in the British Milk Race continued in 1970 when JiÅ™i Mainus of Czechoslovakia won the event. But it was in the two Olympic Games in the decade – Munich 1972 and Montreal 1976 – that Eastern Bloc cyclists really excelled (see Table 4).

At the 1972 Games the Soviet Union took both the tandem and the road team TT titles. The tandem event was discontinued at the 1976 Games but Eastern Bloc cyclists nevertheless won three titles in Montreal and a total of eight medals.

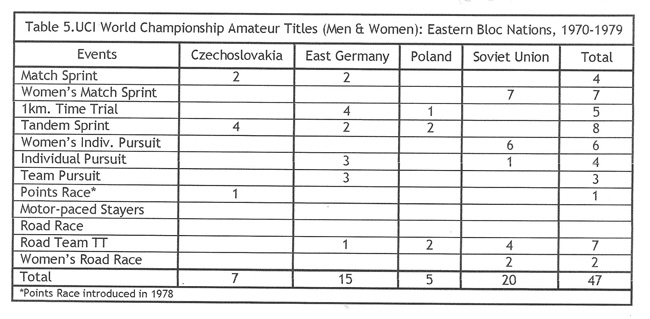

A similar pattern of Eastern Bloc dominance was evident at UCI world championships held during the decade (see Table 5). Women cyclists from the Soviet Union dominated both the match sprint (7 titles) and individual pursuit (6 titles). East German men won a total of 15 world titles on track and road. Czechoslovakian pairs won the tandem title four times during the decade while the Soviet Union triumphed four times in the 100km road TTT.

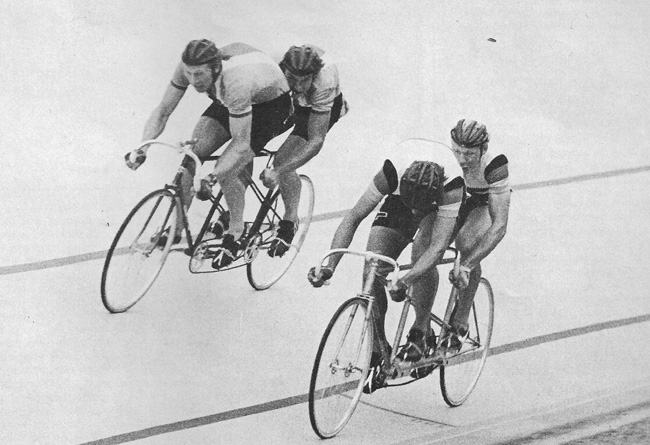

Beginning at the 1972 Munich Olympics, UCI world titles were not duplicated in Olympic years as had occurred previously and thus fewer world titles were contested in both 1972 and 1976. The men’s UCI match sprint title was won twice by the Czech, Anton Tkac (1974 and 1978), while East Germany’s Hans-Jurgen Geschke (1977) and Lutz Hesslich (1979) triumphed in this event. In so doing they replaced the former French sprint superstar, Daniel Morelon.

During the 1970s, Eastern Bloc national teams also successfully competed in amateur road events in Western Europe. British Milk Race winners in this period included:

- 1977: Said Gusseinov (Soviet Union).

- 1978: Jan Brzezny (Poland).

- 1979 (& 1982): Yuri Kashirin (Soviet Union).

However, Sergei Soukhorouchenkov of the Soviet Union emerged as the Eastern Bloc’s international road superstar of the era. His victories included:

- Tour de l’Avenir in 1978 and 1979 (second in 1980 & 1981).

- Peace Race in 1979 (&1984).

- Giro delle Regione in Italy in 1979 (&1981).

- 1980 Moscow Olympic road race.

Over the course of the 1970s, therefore, Eastern Bloc cycling came to dominate international amateur cycle sport on road and track as never before.

The vicissitudes of Eastern Bloc cycling in the 1980s

In 1980, the Olympic Games were scheduled to be held in Moscow. However, the Cold War between East and West suddenly intensified. This was largely as a result of the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, which led to the United States opting to boycott the Moscow Olympics with many of their Western allies following suit. Subsequently, the Eastern Bloc nations retaliated by boycotting the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

As the decade progressed, internal political unrest escalated in the Eastern Bloc nations. In the late 1980s these dramatic developments resulted in the domino-like collapse of state socialist regimes in Poland, East Germany (symbolised by the destruction of the Berlin Wall in 1989), Czechoslovakia and beyond, ultimately reaching the Soviet Union itself. This combination of circumstances was to totally undermine Eastern Bloc competitive cycling but not before its cyclists succeeded in asserting their supremacy in international amateur cycling one last time.

The 1980 Moscow Olympics were virtually monopolised by cyclists from the Eastern Bloc (see Table 6). While the boycott of the Games by the USA and the partial boycott by some other nations were apparent in many Olympic sports, the cycling events remained largely unaffected. In these, Eastern Bloc riders only failed to succeed in the individual pursuit event which was won by the Swiss rider Robert Dill-Bundi, from Bondue of France (2nd)and the Dane, Oersted (3rd).

Eastern Bloc triumphs in European amateur road races continued unabated during the 1980s. A succession of Soviet riders won Britain’s Milk Race in 1980, 1981, 1982 and 1984. East Germany’s Oleg Ludwig took the Tour del’Avenir in 1983 after winning the Peace Race in 1982 and then again in 1986.

The Eastern Bloc collectively boycotted the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics in retaliation for the US-Western boycott of the Moscow Games in 1980. It was at the 1984 Games that a women’s cycling event was first introduced in the form of a road race. This was 26 years after women’s world titles had been first instituted by the UCI in 1958. The inaugural women’s Olympic road race was won by the USA’s Connie Carpenter from her compatriot Rebecca Twigg with West Germany’s Sandra Schumaker third. Subsequently the number of Olympic cycling events for women was to slowly increase.

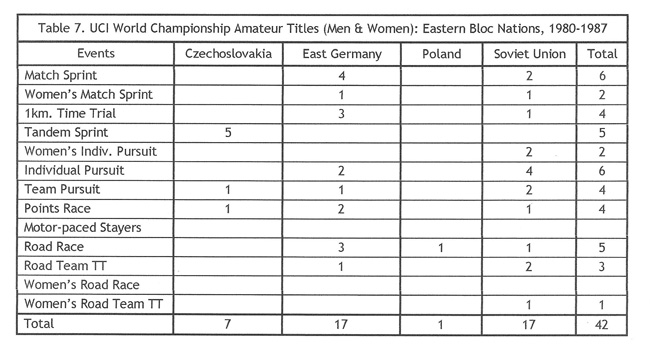

Nevertheless, Eastern Bloc cyclists continued to dominate the UCI world championships during the 1980s. This occurred despite the rising tide of political unrest in their home countries (see Table 7).

It was at the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games that the cyclists from the Eastern Bloc triumphed by winning six gold medals and twelve medals in total (see Table 8). This was to be the last Olympic Games at which the state socialist nations of Eastern Europe would be represented.

The aftermath of the collapse of Eastern Bloc cycling

The sudden implosion of the state socialist regimes in Eastern Europe in the late-1980s/early-1990s was followed by the rapid demise of their systematic training programmes for creating cycling champions. For some of the riders involved it was the end of their cycling careers; for others it meant continuing in the sport under new national identities; for others again it provided an opportunity to enter the lucrative ranks of sponsored Western European cycling teams. The numerous support staff in these programmes – coaches, trainers, sports scientists, medical professionals, soigneurs and mechanics – faced similar dilemmas and choices.

After the Olympic movement abandoned the amateur/professional distinction following the 1992 Barcelona Games, the UCI followed suit in 1993. Both the amateur FIAC and the professional FICP were disbanded and once more the UCI became the single supreme world cycling body. Quite what became of the Eastern Bloc’s cycling apparatchiks who had long dominated the amateur FIAC’s corridors of power and critically shaped its politics and policies is unclear.

Eastern Bloc cycling may have dramatically changed world cycling during the Cold War in the second half of the 20th century but ultimately it was itself irrevocably changed.

References

Printed

Fotheringham, William (2010). Cyclopedia: It’s all about the bike London: Yellow Jersey Press.

Henderson, Noel G. (1973). Cycling Classics, 1970-72. London: Pelham.

Saunders, David (1975).‘Championnats du Monde de Cyclisme, Belgique 1975’. International Cycle Sport, No. 89, October, (not paginated).

Websites

Bike Cult <www.bikecult.com>

Classic Lightweights <www.classiclightweights.co.uk>

Posted: Tuesday 18th August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.