Wood sprints

Posted: Friday 12th June 2020

I can never quite remember how, but as a young teenager I acquired a pair of wooden sprints, or cane sprints as we knew them. I probably bought them on the cheap as most of the cane sprints around were pre-war and owned by older cyclists. Cane sprints, in the main, were used for grass-track racing. They were said to be more lively on the rougher grass circuits. As many riders of the day were hard up they would only have one pair of racing wheels and if they were wood then they were also used for time-trials.

On the track the question of braking never came up but on the road something had to be done about it, although it was not too critical as everyone was on fixed-wheel and you don’t brake much during a time-trial anyway. Most road riders on fixed were proud of the fact that they could travel for miles without touching the brake by using the legs to slow down. In those days no-one used the modern technique favoured by the new wave of fixed-wheel riders, coureurs, posers and the like. Some of these actually risk the wrath of the law (how many policemen know the legal situation relating to fixed anyway?) by riding brakeless. The technique they use is to jump the rear wheel in the air, lock the legs and skid the wheel as it hits the tarmac – good for the sale of tyres and tubs if nothing else.

Back in the old days ‘when men were men, etc.’ it was possible to get cork brake blocks made especially for wood rims (see Bob Freeman piece at bottom of page). I cannot remember who or how many manufacturers produced them but a pair in your collection would be a great talking point.

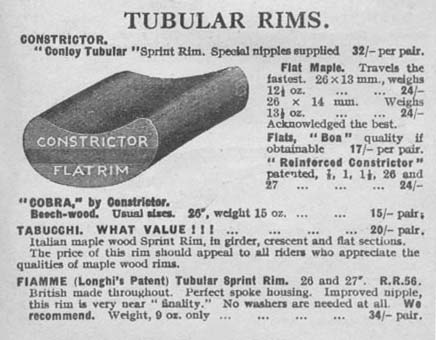

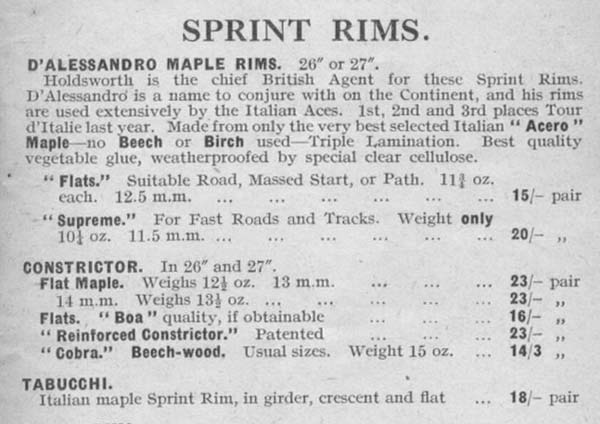

Although known as ‘canes’, wooden sprints were made of laminated maple. If you look closely at a rim in good condition you can see the glue lines. On a neglected pair you can see air between the laminates as they come apart. The strips were very thin and formed around a mould as they were glued and laminated before being machined to the correct profile. This of course was done in the era before the hi-tech waterproof glues were developed during WWII to build aeroplanes – the Mosquito I believe.

I have two cane sprints, both fronts, one 26″, the other 27″ Continental (or 700 as we know them now). Sprint rims and wheels come up for sale now and then. An essential to build the wheel is the extra long nipple needed to go through the wood. Wood rims are still made by two companies in Italy and sold under the trade names CB Italia and ‘Cerchio Ghisallo‘.

See CB Italia wooden sprints built at http://fixedhub.wordpress.com/2011/08/15/wheel-building-with-andy-kelly/

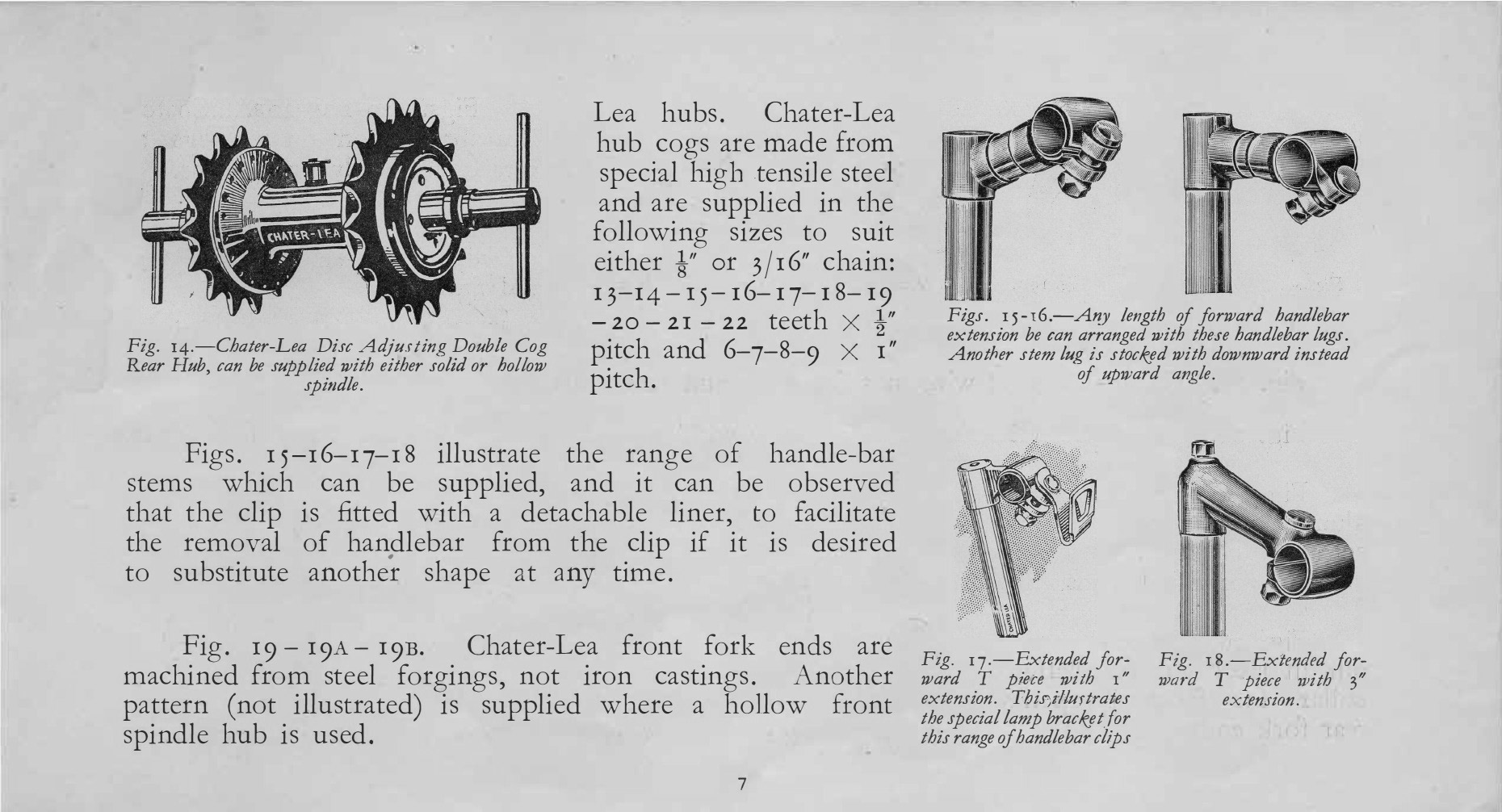

These ‘Vigorelli’ hickory rims (built on Airlite large-flange D/F hubs) are for use in my fixed-machines in rotation and at the moment are shown in a 1976 Mercian Vigorelli track which is fitted with home-made cork brake blocks shown below.

Coureur was a cycling magazine initially owned and edited by J.B. Wadley who travelled Europe every year covering the big cycle races. In his special Tour de France edition of 1956 he mentions that a huge mobile workshop followed the Tour and inside were dozens of wooden sprints. “These were claimed to give better braking conditions on long mountain descents. But this year they were not popular, and as far as I could see, only Geminiani of the ‘big boys’ was using them” Maybe this was the time they finally lost out to the alloy sprint rims favoured by most serious racers of the time. That is until some fifty years later when wood rims became the choice for selected builders of individual custom machines and they became readily available to restorers of old classic lightweights.

In Cycling dated October 18, 1929 there was an article entitled, “Putting Sprint Wheels to Bed”. We have permission from Cycling to use the early material we will reproduce it here:

The sub-heading is “Moisture Spells Ruin for Wooden Rims. The Following Hints Will Help You to Preserve Them”

“The fine weather which has favoured most of the current season’s road events has been of clear financial benefit where such vulnerable racing materials as wheels and tyres are concerned. One coat of varnish will have seen most sets of wood rims through the summer without the fears of their “impending dissolution” that beset a racing man during wet seasons. And tyres too, should not be much the worse, apart from punctures.

Damp Dangers

Racers who have “packed up” until next spring should not, however, be tempted to store their wheels and tyres without first giving them very careful attention, for it is during the winter, with its frequent moist atmosphere, that damage is most likely to occur, even when the equipment is unused. This is especially the case when 13mm track rims are in question. They are frequently used with satisfaction on our smooth modern highways, but their susceptibility to damp (which they are not designed to combat) is notorious.

During the course of a visit to the Constrictor Tyre Co’s factory recently we were shown a wheel which has been suspended in a corner of normal dryness for a period of twelve months. We were informed that during the year the variation in the wheel’s diameter amounted to about 3/16″. Month-to-month tests showed that almost all of the expansion had occurred during the winter. When we saw the rim it had contracted to almost its original dimension but – note this carefully – its circumference was flatted at every spokehole and close examination revealed the edge as shaped in a series of waves.

Uneven Expansion

Here is the explanation as provided by Mr Bane, the Constrictor manager, who has thirty-years of experience in the wheel and tyre world. When the wheel was hung up it was tensioned exactly as for racing. Every spoke had the requisite tautness and the rim presented an even circle. As winter drew on and the air became correspondingly more moisture-laden, the wood of the rims endeavoured to expand, but was prevented from doing so properly by the tension of the spokes. Thus the rim swelled between the spoke nipples and was held in place where the nipples fastened, at which point the texture of the wood (since something had to happen) became compressed. The result of this dual process was that with the return of dry weather contraction was uneven, and the rim lost its true circular shape – a fact which at once became evident when the wheel was subjected to a road test.

Preventive Measures

Since the rim used in this experiment was of high quality, it is obvious that it was less likely to yield to atmospheric action. It follows that especial care is necessary where the materials used are of the type known as ‘second quality’, or where there are doubts about the craftsmanship that has gone to the building of the wheel. The following preventive measures, based on a study of the experiment just described will, if followed, enable readers to store their racing wheels without fear of climatic damage. With a nipple key, loosen each spoke half a turn, then go round the wheel again to complete a full turn, (The object of carrying out the task in two operations is to release the tension gradually; otherwise the wood may tend to split or loose its shape.)

Using a very fine sandpaper remove all traces of roughness caused by brake-block action and wash the whole of the rims with a rag moistened with petrol. In performing this operation care should be taken not to remove any transfers as these are private marks for manufacturers’ reference. Finally apply a a thorough coat of quick-drying varnish (we understand that a brand especially prepared for the purpose will shortly be put on the market by the constrictor tyre Co.) and hang the rims in the dryest place available without actually subjecting them to any considerable degree of artificial warmth. During the damp weather the rims will swell but the return of summer will find them back to their normal dimensions and shape, the latter being due to the absence of tension whilst the expanding action is in process. Re-trueing of the wheel should be entrusted to an expert, who may be relied upon to obtain the exactly correct spoke tension for road and track use.

Keep Tyres Inflated

So far as tubular tyres are concerned, practically all that is necessary to maintain them in good condition is to fit them to the re-varnished rims when the latter are dry and inflate them to half pressure, testing every now and then to ensure that the pressure is maintained. Store them if possible in a fairly dark place (light is harmful to rubber) and protect both them and the rims with a wrapping of brown Kraft paper. They should of course be hung from a peg, out of contact with the ground. It may be mentioned that the best temperature for tyres and wooden rims is in the neighbourhood of 40 degrees.

When I first built up some Ghisallo wood rims for my road bike, I tried Campagnolo pads on them. They made a horrific screeching noise and left black crud on the rims.

So I made some cork brake pads from corks out of a few bottles of Chianti Classico and put them on. Success! So far anyway in trials just around the parking lot. Tomorrow I will try them for 40 miles or so and see how it works.

To make, I cut them to a rough shape using a hack saw, then to a pretty close shape on the belt sander, then put the little divots in to make them fit in the holders with a file. Pretty easy, about 10 minutes per pad total. And a lot cheaper than Campy brake pads!

Posted: Friday 12th June 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.