Building classic tandems

Posted: Friday 26th June 2020

I know very little about tandems but I do know that several builders of classic frames constructed them. I hope that those with more knowledge on this subject will submit material to give this piece some depth.

In the same way that solo frames would be built to suit time trialling, track racing and touring, tandems all had their own characteristics. One difference however is that whilst, in the main, most solo frames were built to the basic triangular format, tandems offered a range of solutions to the question of stiffness for this much longer construction which had to absorb the power of two riders.

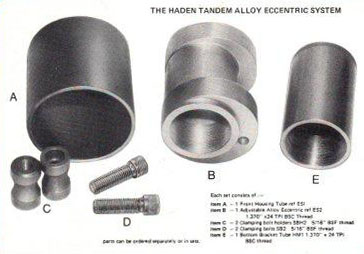

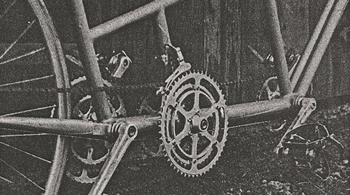

Building up tandems also involved choosing components to deal with the particular challenges of gearing and braking for two riders, the most basic being the use of in-line or crossover format for the drive chain. The problem af adjusting the chain between the front and rear chainwheels was often solved by the use of an eccentric (off-centre) bottom bracket which rotated in an oversize bottom bracket shell and which was secured by two pinch bolts. Others used a spring tensioner to take up any slack between the front and rear chainwheels as seen below on this Pennine tandem where the tensioner is mounted on a lamp bracket boss brazed onto the tube between the two bottom brackets.

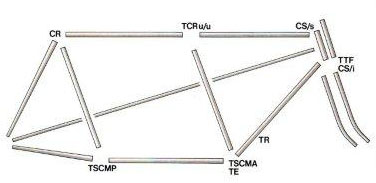

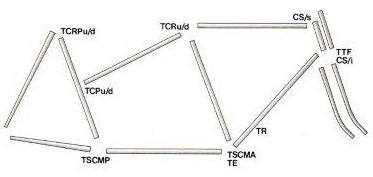

Construction of tandems entailed the use of different components, special tubing and special lugs to accommodate configuration of tubes not seen on solo frames. Shown below are tubing sets for a double gents Marathon and a lady-back open frame. These tubes will be of slightly larger diameter to give the extra strength needed.

As can be seen from the Marathon tube set above, lugs are needed to join tubes in a way never used for solo frames.The complexity of the joins encouraged some builders to use brazed (welded) construction as this gave greater flexiblity of design, not being constrained by the lug angles available. I asked John Spooner who supplied these building images if he used a jig to build tandems as this would be mighty piece of kit used but rarely. He explained that he built the front main triangle and checked it for trueness, then added the next triangle which was checked and then the rear triangle. He built both brazed and lugged frames.

Some of the lugs used for tandems are shown below. The clamps to lock the eccentric bottom bracket can be seen in the first illustration. Both bottom bracket shells accommodate the large diameter tube used between them.

Braking these heavier machines was also a problem with various combinations of cantilever, hub, side-pull and centre-pull brakes being used. Sometimes they were doubled up to give three or four brakes and it was even known for the stoker to have a lever to use when their nerve cracks! Mafac made a brake lever which took two cables to different systems on the same lever. The person steering the tandem is known as the captain whilst the rider at the rear is known as the stoker.

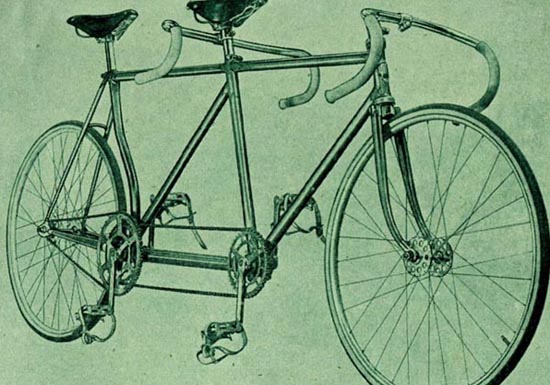

I suppose it was Geoff Waters’ submission on tandem racing racing in South Africa which started me thinking about this subject as it raised a few questions in itself, such as the names of the various constructions. Mick Butler explained the names of different frame constructions. The most basic form was known as the open frame. The frame below is almost an open frame but there is an extra tube from near the top of the front seat tube to the rear bottom bracket.

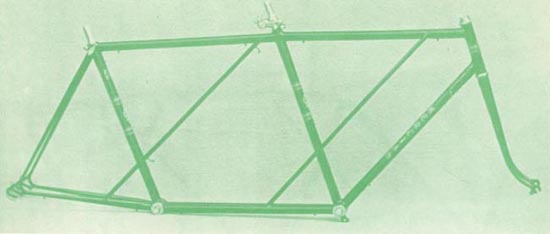

The addition of a tube from the head to the rear ends (splitting into two to form additional stays at the rear triangle) was known as the Marathon.

The Double Marathon had such a tube from the rear end to the rear of the front seat tube and another tube from the head to the rear bottom bracket, which is shown below on a fairly modern tandem with sophisticated time trial equipment.

The Direct Lateral had a tube from the top of the head tube to the rear bottom bracket. To these designs can be added the option of a double triangle or ‘lady back’ design and the use of single normal or large diameter tubing or twin small diameter tubes. The tube joining the two bottom brackets came in various diameters and profiles.

Another tube on the tandem to receive its own styling was the rear seat tube which could be normal on some machines and curved for those willing to sacrifice comfort for the performance enhancement of the resulting shorter wheelbase. This concept was synonymous with Claud Butler’s Ultra Short-wheelbase design but it was also used by many more builders of customised frames.

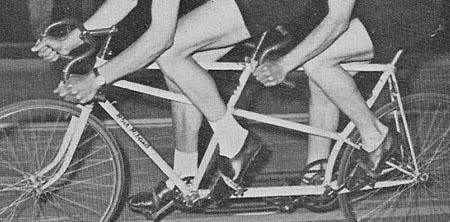

All of the frames shown above have had in-line transmission. Some frames used a crossover transmission, especially if multiple rings were wanted for the rear drive. Those here are both track frames used in South Africa.

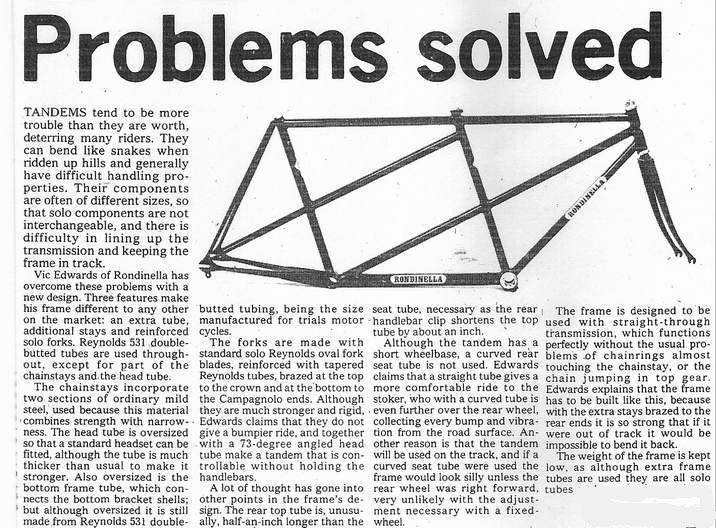

It soon becomes apparent that by combining these options a huge variety of designs became available to the tandem builder. The article below explains the thinking behind the Rondinella pictured in action above:

Bill Philbrook and Jeff Lyon produced a number of tandems with intermediate chain wheels as a step down device. They apparently solved a number gearing problems and only added minimal extra weight.

The adventurous frame builder didn’t have to stop at the tandem as shown by the Jack Taylor touring triplet shown above:

Posted: Friday 26th June 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.