Ephgrave Lightweights

Posted: Saturday 16th May 2020

Les Ephgrave initially learned the art of frame building before WWII from his first employer, Harry Rensch of Paris Rensch Cycles. He moved on from Paris to Claud Butler where again he was employed as a frame builder until 1948.

At this point he decided to set up his own business ‘Ephgrave Lightweights Ltd.’ at the Avertey Works in East London. It is thought that he had produced some frames of his own before this date, probably whilst at C Bs. He was helped in the setting up of the business by Rory O’Brien and in return he built O’Briens top-of-the-range models for him.

He was to produce high-quality frames with the emphasis on finely filed and decorative lugwork although in common with other builders at the time he produced some sif-bronze welded frames. As with all other frame builders in this period of austerity Les was having great difficulty in obtaining the materials with which to produce his frames. To make the ‘welded’ frames more attractive to the dyed-in-the-wool buyers he decorated some of these frames with long pointed bi-laminated lugs with a curl on either side, a skill he would have learned at Paris and C B as they both produced frames using these methods. The welded frames had a 1â…›” top tube, a practice most builders followed.

The lugged frames were known as ‘The No. 1’; ‘The No. 1 Super’ and ‘The No.2’ designs. The early lugs were cut from the Ecla Belgium malleable lugs according to his brochure. Later on they were based on Nervex lugs which were modified and improved in the frame-building workshops. The emphasis here was on quality, where the lugs were cut, filed and feathered to a very high standard and to this day this is what makes Ephgrave frames a favourite of the serious collector. The top of the range No. 1 Super had extra windows cut into the lug used for the No. 1, lug which in itself was more intricate than the No. 2 which was based on a Nervex Serie Legere lug. From about 1953 the headlugs of the No. 1 acquired a spearpoint on the front of the head tube (image top right). Some of the number 2 lugs were embellished by having ‘swallowtails’ added to the head lugs – these were behind the head tube, top and bottom

In the 50s two frames were produced using the name ‘Italia’. The first had a lug cut to the pattern of an arrowhead whilst the later ones ,1960s, were produced using the Prugnat lugs with the spearpoints split and curled in some cases. A number of the frames had decorations on the tops of the seat stays. Some had a simple metal strip (see images below) whilst the others from about 1953 could have what are popularly known as ‘Lollipops’.

The Ephgrave catalogue cites three recommended designs for Massed Start Racing, Track and Club Riding, which is surprising as time-trialling was probably the most popular use for the Ephgrave frame since road racing cyclists had a preference for the plainer, continental style lugs. It also recommends that frames are built square, i.e. top tube and seat tube of the same length.

Most of the headtubes were adorned with an ‘Ephgrave’ transfer but some had an aluminium plate which may have been printed or used with a transfer on them. The down tube transfers were Old English block lettering until towards the sixties when a script alternative was offered.

All Ephgrave frames are numbered with the prefix ‘LE’ both on the frame and the fork column, Peter Holland, V-CC marque enthusiast, can help with dating. Records show that L E produced in the region of 4000 frames before he died in 1969. A few of his frames were produced for other shops such as Rory O’Brien as mentioned in the first paragraph.

An interesting set of images (below) from Hiroshi Asada in Japan of his 1952 Ephgrave LE 1013, showing construction details on a ‘raw’ unpainted frame. The frame has braze-ons for Osgear and we show the under bracket braze-on for the tension arm. These brackets position the arm lower and improve the chain tensioning.

The lugs are No.1 Super Bilaminated. Peter Holland has heard of framebuilders having great difficulty in repairing what at first was believed to be a lugged frame and then having started work on the repair to find that they have a much more complicated job in repairing a frame built using bilaminates. This happened with the repair of his Ephgrave 263LE in 1991 when the bottom bracket was replaced together with a new down and seat tube. This one shown below is more apparent in being a bilaminated frame as some of the joints are partly sif-bronze brazed.

Les told me in 1963 or 1964 that during the Second World War he and other cycle builders were employed building special reconnaissance Spitfires. They were specifically recruited because of their skills and experience in welding and/or silver soldering thin tubing. It was my understanding that Reynolds 531 (‘Five-three-one’) was chosen by the Air Ministry for these special hand built Spitfires. Why not for bicycles?

The article cited below prompted my recall:

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/spitfire-norway-mountain-great-escape-pilot-found-second-world-war-nazi-raf-espionage-alastair-gunn-a8646841.html

As I have mentioned before I am somewhat fascinated by the bilaminated method of building frames and have used the technique on quite a lot of occasions for a variety of differing reasons; if nothing else the bilaminated technique offers the builder a terrific amount of freedom, particularly if he is intent on building custom i.e. made-to-measure frames as opposed to standard models.

There has been a considerable upsurge in the amount of interest shown by collectors in frames built with this method, but, in my opinion there have been many false assumptions and interpretations. Into this category falls, I am certain, the Ephgrave No1 Super ‘Bilaminated frame No 263LE that you have just featured in your pages. This frame is an example of the earlier model that did not feature long spearpoints; all the frames (or rather all the No1 frames that I have seen with the early pattern lugs) have been built with EKLA malleable cast lugs.

These lugs with their very thick walls and ‘cheeks’ are cast in a precise angle and the holes for the tubes are machined /reamed at that angle. Although the lugs are named as ‘malleable’ they cannot be reworked, bent, blacksmithed etc etc to take on any other angle without great difficulty and also without the danger that the holes would distort, rendering quite expensive lugs worthless.. destined only for the scrap box.

As your article states, supplies of frame parts were often difficult to obtain in post-WWII Britain, and under these circumstances no frame-builder would take that risk. The red No1 Super frame with the extra windows and the spearpoint embellishment of the headlugs is a later frame whose lugs are not malleable cast, but in fact pressed steel plate. Unlike the malleable ones these lugs can be reworked into different angles quite readily. Having studied the photos of the MkI No.

I Super frame and enlarged them, I am convinced that the frame has not been built by the bilaminated system. Instead I think that Ephgrave had decided that this particular frame needed angles that differed from those offered by a standard set of EKLA lugs. Because it would have not been feasible to adapt or rework the cast EKLA lugs he decided to alter then by cutting, by sawing off , the pipes from the lugs ie separating the top-tube pipe from the head-tube one. These pipes would then be brazed to the tubes, the ensembles would be mitred to the required angles and then the lugs bronze-welded back together

One way to alter the angle of a pressed steel lug is to make saw cuts on both upper and lower faces of the lugs and then to insert tubes into the pipes and gently bend and persuade the relatively thin steel sheet to adopt the required angle. This would not be possible with a cast lug without the danger of either the casting breaking or the holes distorting If you examine a bronze-welded joints on most bilaminated frames, when they are in the raw steel state, you would note that the beads of sif-bronze welding material are more substantial than those on the EKLA lugs.

You don’t have to examine the photos of the three lugs too closely to notice that there is more bronze weld bead on the upper head tube and the seat tube lugs than there is on the lower head-tube lug. You will also notice that the top-tube pipes on both the upper head-tube lug and the seat-cluster one are longer and more substantial than the down-tube pipe on the lower head-tube – this latter lug having only a very small amount of bronze bead..and certainly not a full continuous bead that encircles the whole joint.

This leads me to conclude that Ephgrave cut both the upper head and the seat lug in half in order to reprofile the angles but was able to alter the less robust down-tube lug by just putting a saw nick in the upper angle and very carefully ‘pulling’ the angle The fact that the chainstay-to-bottom brackjet pipes are missing leads me to think that the change in angles also dictated a slight change in the bottom bracket height and chainstay angle. Because the chainstay pipes were so short and incapable of being reworked, Ephgrave decided to dispense with them altogether. I think that this theory holds water and is justified by the fact that the frame uses an Osgear fitted to a bracket brazed underneath the bracket shell as opposed to having the tension arm clamped around the lower end of the down-tube.

The difference in location of the arm would render the pulley lower,and nearer to the ground. I think that Ephgrave actually raised the bracket height to give extra ground clearance to the pulley. All of which is my personal interpretation of how Ephgrave constructed this particular frame. If nothing else my thesis should provoke some reflection on the part of collectors of Ephgrave frames. I reckon that if you could assemble a random sample of about twenty early No1 Super Ephgrave frames and sand-blast the paint off all of them..you would find more….falsely identified bilaminated frames.

Derek Athey relates that he was very fortunate to have befriended an elderly gentleman by the name of Geoff Bolwell (V-CC, FCOT, TCC, Buckshee Wheelers etc) who, when demobbed, got a job with Claud Butler in 1946 as a buyer for their works and retail shops. He worked with all the great names of the era…Ephgrave, Skeates, Purves, Gray, Philbrook etc etc. By 1950 he left to join Brown Brothers as a rep and then frequented the retail and business workshops of these men.

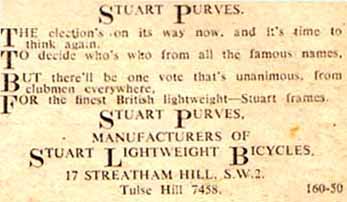

Geoff knew the background to the relationship between Ephgrave and Purves when Ephgrave left to start on his own. Apparently Purves wanted to join forces with Les, but Les was reluctant to do so as he wanted to work close to is home in East London, whereas Stuart was keen to have the joint operation in Streattham, south west London. They couldn’t agree but initially attempted to work separately from different locations but all work was to be channeled through to Aveley Works.

It very quickly became apparent that the relationship didn’t work as Purves’ business style didn’t match that of Les’, hence the different advertisements supplied by Alvin below. Stuarts passion for horse racing and betting meant that very little serious input was forthcoming. Geoff frequently commented that Purves was almost never at his premises when he finally established his own business in Streatham. Sadly Geoff has now passed away.

Ephgrave and Purves from advertisements in Cycling

The story from these few advertisements appears straightforward, but what the story I read doesn’t tell us is how these men worked together- for that Peter Holland’s and Mick Butlers’s accounts are far superior.

There are persistent accounts of how Ephgrave, when still in employment by Claud Butler, made frames for sale to clubmen (perhaps selected athletes whom he favoured) and sold them at competition events from 1946 onwards. When I bought my frame the original owner was said to have purchased it in 1947 – just unfortunately though it carries the number LE 1612 and must therefore be a 1952 frame- memories and vendors don’t always play fair! Incidentally, the first time I could find an Ephgrave cycle offered for sale was in Cycling’s secondhand sales column for 7 July 1948; isn’t that a more reasonable time to find such a machine?

In tracking adverts for Paris Cycles in Cycling a few years ago I came across the advertisements described below. They appear to tell a tale. The first one was on 14 April 1948. This was placed therefore placed some two months before Peter Holland says the firm was registered (June 1948). In it, Ephgrave Lightweights made their first announcement using a layout that seemed to become a house style with its inset text items, opening and closure by the firm’s name with overlarge initial capitals and the figment of bureaucracy implied by the “The Secretary”:-

This series of advertisements never appeared again in Cycling and indeed was probably never needed – the small firm had more than enough work on. Who was the Secretary –was that Les Ephgrave’s brother? Or could it have been the butcher whose shop window also served as a display area just around the corner on Upper Clapton Road?

All these advertisements stand out from the rest of the advertisements in Cycling –they have an elegance of layout, an almost lyrical approach in their choice of words and phrasing but they stop short of just one attribute –rhyme.

Now look at a separate advertisement that can be found in Cycling for 25 October 1951 –and remember the rest of the world had moved on since 1948. But look at the layout, the capitals, and the ideas.

Interesting to consider where else we have seen such a lay out –with a slightly off beat approach to selling bicycles – and just look – now we do have rhyme! Of course the two sets of advertisements could have come from the same small or even large firm of advert copy writers – but I prefer to think the evidence suggests that all of them came from the pen of Stuart Purves!

Following on Alvin’s piece above, two readers, Derek Athey and Mick Butler, have pointed ot that this advertising style is in fact an in-house style used by Cycling for many of its small adverts.

Bryan Clarke has this 1952 Ephgrave No1 that includes its original fancy lugged Ephgrave stem, Gnutti headset and C1000 chainset. He has never seen a ‘chromovelato ‘ paint job on any British frame let alone an Ephgrave. Also this is the first Ephgrave made stem he has ever seen in 30 years of involvement in retro bikes.

It is a copper vanish over chrome and is very old I have no doubts about it being original.The forks were the same once but the original owner painted them silver when the finish deteriorated. It must have looked spectacular when new.

In his early years Les Ephgrave produced some bi-laminated frames where the frames were welded up

with ‘bi-laminate lugs’ brazed on. This is frame number LE400 made in 1948/9.

SOME CLASSIC EPHGRAVES

Some builders brazed the bi-laminates to mitred tubes and then these were brazed to each other.

Other builders, such as Paris, would have carried the bi-laminates around the head tube.

Posted: Saturday 16th May 2020

Contents

- Overview

- Intro to Ephgrave

- Early Designs

- Frames

- Images from Japan

- Lug Gallery

- Quote from James Grundy

- Quote from Norris Lockley

- Frames

- Lugs

- Quote from Derek Athey

- Research from Alvin Smith

- Adverts

- Advert Followup

- Stuart Purves

- Quote from Bryan Clarke

- Bryan Clarke - 1952 Ephgrave No1

- Copper vanish

- Ephgrave Images

- Bi-laminated frames

- Frame number LE400

- Classic Ephgraves

- Images

- Early Years

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.