Hanlon, Pat

Posted: Thursday 04th June 2020

When Peter Underwood bought a 1973 Pat Hanlon several years ago it prompted me look at my own example, purchased from John Pavey in the mid 1990s. I knew nothing about the model nor date – only that when built up it was one of most delightful bikes I had ever ridden. With distinctive lugs, a 39 ½” wheel base and angles of 73 degrees parallel it was designed I supposed for time-trialling or road racing but handled comfortably on the poorest of road surfaces offered up on many an English country lane.

At the same time, Peter came into possession of a copy of Pat Hanlon’s 1967 catalogue, which revealed that my frame was an ‘Ultralite’ model, identified by the style of the lugs. However, the lug pattern on Peter’s frame could not be found and must mean that the model types had changed or simplified by the time it was built in 1973. In the mid 1970s Pat’s shop changed address, a victim of a new housing development in South Tottenham. The move took her from 175 High Road, N.15 where she had been since 1963, to smaller premises at 77 Bowes Road, Palmers Green, N.13 on London’s busy North Circular Road.

However, she had started out a few doors down from 175 at 179 High Road in 1959 and by April 1960 had unveiled three road and track models under the names ‘Del Premo’, ‘Bianchi’ and the ‘Cresta’ in the pages of the Sporting Cyclist. In July that same year these designs were confined to the track models whilst ambitiously introducing four new road models under the names ‘Sapphire’, ‘Flamingo’, ‘Swallow’ and the ‘Club’. Clearly these models had changed by 1967 to the ‘Professional’, ‘Ultralite’, ‘Criterium’, ‘Giro’, ‘Courier’ and ‘Club’ as well as a model described simply as a ‘Track/Time Trial Model’.

The frame number on the Peter’s 1973 model was 203073 and this suggested that a year of build existed as part of the numbering system in common with a great many frame builders from Claud Butler to Gillott. The ‘Ultralite’ frame number was 82068, which offered me 1968 as the year of build, but also alluded to some sort of straight sequential numbering system being used for the first set of numbers. If taken at face value, it suggested that on average, 242 frames were being built each year over the five year period between the two models; surely too many for a relatively small establishment.

What was needed were more examples to test the hypothesis. Help was at hand in the shape of a bike owned by Graham Brice. Using the lug pattern as a guide, it showed Graham’s frame to be a ‘Professional’ model, a combination of fancy lugs, contrasted by sleek ‘Cinelli’ style sloping forks and shot-in stays. For the lightweight enthusiast there can be no finer looking machine.

The previous owner told Graham that the frame dated from 1968, but with the number being 103069, implied that it was made a year later if my assumptions were correct. It is curious that a zero appears just before the assumed date on all three frames and an alternative explanation is that this could have acted as a space after the total build that year. Whatever the outcome it seems clear that the last two digits at least represent the year of build in each case. No doubt more examples will help unravel the exact truth. In fact, Patricia Killiard owns what is thought to be Pat’s own 19½” frame which is simply stamped with the number 82 to add to the confusion. Both the 1973 model and my ‘Ultralite’ have fastback stays, a popular feature on time trial bikes that survived well into the 1980s. All four models have customised or hand-cut lugs.

Pat Hanlon started out as a wheel builder for Macleans during WWII, for which she was to become supremely expert and best known. It was a difficult business for a woman to enter at a time when only men were employed as mechanics. It is thought that from 1964, Tom Board built a large proportion if not all the frames and worked at the back of the shop in Tottenham after first leaving Macleans when they closed down in 1962 and then Fred Dean. It is said that he continued to build her frames until 1979. Hopefully I will be able to make contact with him in due course to verify these details.

At present it is not known who built the early models. In conversation with Simon Carter some years ago Tom maintained that both he and Vic Edwards were responsible for building the frames. The shop remained open until 1983 when Pat retired to live in Majorca: she passed away in December 1997.” ( NOTE that Simon Carter now owns frame no 208074 and once owned a 1964 model which he believes was stamped 442).

Richard Fox adds that at the Comrades CC headquarters in Quendon Essex there is a memorial tree planted to Pat Hanlon. He parked his car next to it last Saturday.

I am indebted to Graham Brice, Mick Butler and Peter Underwood for their assistance in researching this article. Mick has since unearthed some more information on Pat which continues below the following images.

Further information about Pat Hanlon:

Since writing the above web page further information has come my way with regard to this marque,

Some time ago, Simon Carter alerted me to an advert from a 1958 copy of ‘Cycling’ for Tottenham Lightweights at 179 High Road N 15, Pat Hanlon’s first address. A Tottenham Lightweights frame which made an appearance at a Ripley jumble displayed an identical head tube transfer design to the ones used by Pat on her bike frames at all three addresses (see photo right- compare with image at top of page). It suggests that after leaving Macleans in 1957 she first set up under this name before converting to her own name a year later or that she took over an existing business.

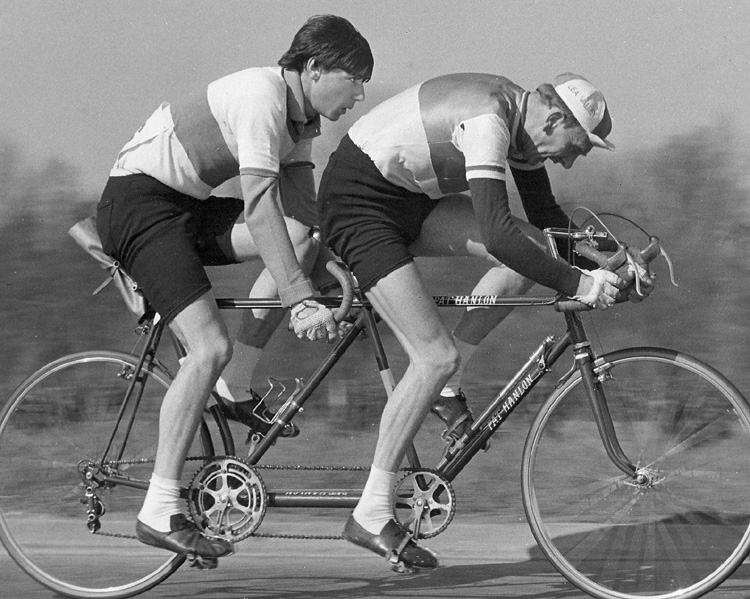

Two, three and four figure numbers have been found on her frames seemingly before new models were launched in 1967 that have the number sequences described in the article above. This probably coincides with the employment of Vic Edwards as her frame builder. Vic was responsible for building Alf Engers record breaking bike for Alan Shorter in 1969 and most likely the Pat Hanlon (?Ultralight) that Tim Dobson rode to become the first person to achieve a sub 21 minute ‘Ten’ on the road in 1971.(see photo below)(Cycling Weekly 22nd June 2006)

Richard Fox whose family were very close to Pat has stated that when Vic became ill (?mid1970s) she turned to Vic Coffin to make her frames for several years before he too became ill and was gradually superseded by Tom Board. After giving up the Bowes Road shop she continued to build wheels and trade from her own address in Dagenham with Tom as her frame builder. The bikes she supplied at this time had plain vinyl transfers without an address. Richard never heard of Les Ephgrave building any of the earlier frames and this seems out of the question based on information supplied by Roger Chamberlain recently. However an article about Tom Board in the Bicycle magazine from October 1983 states that Tom rented a workshop at the back of Pat Hanlon’s shop in 1971 after leaving F W Evans to build for her and Condor. It suggests that the situation at this time was far from clear cut.

Thanks go to Graham Brice, Simon Carter, Roger Chamberlain and Richard Fox

Bryan Clarke

November 2008

Pat Hanlon’s son Tony worked in the shop alongside his Mother as a mechanic and wheel builder, Pat’s husband was called Jim. There is a little about her in the new Fellowship News. I also found out that for 10 years she worked as a waitress (Nippy) in J. Lyons Corner-House teashops. But it was the bike she lived for, thinking nothing of cycling to Somerset and back at weekends to visit her parents (a minimum of 18 hours each way), or rising at 3am to join friends for 90-mile rides before the afternoon shift. With her yearly mileage approaching 15,000 miles, including impressive feats in racing, she had progressed to using custom-built lightweight bikes, one of which she ordered from Macleans, a famous bicycle shop in Islington, North London.

She took to hovering about the shop, especially on busy Saturday mornings, provoking the “guvnor” to tell her to lend a hand. She did it for no pay but her real interest was in the old wheel builder in the basement. She used to watch him and beg him to teach her but, on the grounds that “women don’t do jobs like that”, he refused. It was the Second World War that enabled her to fulfil her dream. With the young men otherwise occupied, one day the “guvnor”, Mr Bailey, barked: “You want to do wheels, you be here on Monday morning.” She stayed for 18 years, until Mr Bailey retired. At first male prejudice both behind and in front of the counter was rife. She was told she should be at home looking after her child (in 1938 she had married a fellow cyclist, Frank Hanlon, and had a son) and that they would never let a woman build their wheels. But Pat Hanlon, all five foot of her, would let it go over her head. She knew she could build wheels better than anyone.

After leaving Macleans she acquired her own bike shop, first in Tottenham, north London, and then in Palmers Green. She ran it single-handed, her marriage having failed. But the shop was just a business. She much preferred to be in her workshop with her wheels. In the beginning she built all her own. Later she could afford to buy in the cheap wheels and concentrate on building the best, selling as fast as she could build. In 1979, aged 64, Pat Hanlon remarried, Jim Clark, one of her reps, and reluctantly began to contemplate the dreaded day, as far as she and her customers were concerned, of her retirement. Just after she finally shut up shop in 1983, Jim died.

I think you will find that Les Ephgrave built some of the fancy lugged Hanlons and Stan Pike also built for her. Stan’s son is still alive and I will see if he can verify this if it is correct.

My friend Keith and I knew Pat Hanlon well. We spent Saturday afternoons having cakes and tea in Pat’s back room at Tottenham. Pat was always building wheels and chatting. My first two bikes were made there, and I am enclosing a photo of my track bike in time trial mode (below), which was built in the 60’s. It was fitted with sprint rims on Campagnolo hubs, Cinelli bars and stem, Unica Saddle with Campagnolo seat post, Campagnolo pedals.

A decade and a half after her death, Pat Hanlon’s name remains one of the most hallowed in the cycling world. However, few younger riders and fans know how she achieved her fame, let alone anything about her.

Prissie Jane Howells (as she was then known) was born on this day in 1915 and spent her early childhood in her native Cardiganshire, doing well academically but suffering a series of lung complaints due to the damp Welsh weather, so her parents decided to move her to Somerset. The drier weather suited her and she became healthy; however, as Welsh was her first language her studies went downhill fast. When she was 14, she was given a bicycle as a gift and discovered a talent for repairing it – a skill that in those days, despite the work carried out by women during the First World War when they had maintained machinery on farms and in factories while the men were away fighting, was considered most unbefitting a young lady.

Two years later, Pat went to live with an aunt in London and spent the next decade working as a “nippy,” a waitress in a Lyon’s Cornerhouse teashop. Often, she would wake at 3am to join the local cycling club for a 150km ride before returning to London in time to work the afternoon and evening shift. At weekends, she would ride to Somerset and back again to visit her parents – around 36 hours of riding in total. Soon, she was covering more than 24,000km each year and began to enter races; immediately enjoying some success which encouraged her to seek out a quality racing bike and finding one at McLean’s, a famous bike manufacturer and shop based at 362 Upper Street, Islington (it closed in 1962), and she began to hang around the shop badgering the owners for a job. They would occasionally give her a job to do, but rarely if ever paid her for it.

The cellar at McLean’s was the domain of the shop’s elderly wheel builder – a man who, like many of those of achieve expertise in the art, gave the impression of being as much a wizard as a mechanic. She pestered him, too, trying to persuade him to teach her the skill, but he refused and told her that “women don’t do jobs like that.” Just as the First World War had forced Britain to give women the chance to prove they were equal to men, so the Second World War proved to be the opportunity Pat needed: one day, with the male shop staff all away fighting the Nazis, the boss told her that somewhat gruffly that as of the coming Monday she would be the on-site wheel builder. She remained there for almost twenty years.

At first – and as one might suspect – Pat faced awful prejudice, with many of the shop’s customers making it perfectly plain that they would not be buying nor even trying wheels built by a woman. Pat, meanwhile, knew her wheels were good and refused to give up. In time, reports began to filter back from the more enlightened customers and those who bought their wheels without knowing who had built them – Pat’s wheels were not good, they were excellent; magnitudes better than anything those who were fortunate enough to own them had ever ridden, light and strong and staying true on even the harshest roads.

Word of mouth is the best advertisement available, and in 1957 after her first marriage failed Pat left McLean’s to set up her own shop in Tottenham (where, in the 1960s, she would employ a young man named John Berrisford; the very same one that taught your humble author how to build a wheel in the late 1990s). By this time, she was famous among cyclists throughout Europe and the great riders of the day would travel hundreds or even thousands of miles to buy Hanlon wheels. She was rarely seen in the shop, preferring to pay shop staff to deal with the likes of Jean Stablinksi, Jacques Anquetil, Tom Simpson and Rik Van Looy (who may well have been riding on Hanlon wheels when he won Paris-Roubaix on this day in 1965 – (see above) when they showed up to buy the wheels she built in her private workshop.

They sold as quickly as she could produce them: Mr. Berrisford told me that, in an attempt to meet demand, Hanlon would take her work home with her and build wheels while sitting down and watching television in the evenings, just as many women of her generation would knit. However, demand outstripped supply, and winning a Tour de France was by no means a guarantee that stock would be available when a hopeful cyclist visited in search of them.

Pat remarried in 1979 at the age of 64, sparking rumours that she would soon retire and sending shockwaves through cycling as riders realised that the supply of Hanlon wheels would soon dry up forever. She continued for four years, finally calling it a day in 1983 – sadly, husband Jim died soon afterwards. She outlived him by fourteen years, dying in Majorca on the 29th of December 1997.

Some of those riders fortunate enough to have been able to lay their hands on a set of Hanlon wheels still have them, and some still use them. Mr. Berrisford’s dated to 1964, and he claimed that he had never had to true them.

You may be interested in some details of my own Pat Hanlon frame which was ordered in 1964 by Phil Tamplin, my old club-mate in the Southgate CC. Phil was the envy of his pals in those days – he was still single and, in his job as a linesman/rigger for the CEGB where he spent his working hours with extensive overtime up in the air at the top of electricity pylons, he accumulated a seemingly bottomless pit of disposable income. This is Pat’s rare Track/Time Trial Model which, I believe, she labelled The Swallow.

Phil did some decent times in the longer distance time trials and decided to invest in a state of the art machine to try and better them over the shorter distances. He chose Pat Hanlon to advise him and eventually his Swallow came to fruition. Money being no object, Phil was able to indulge in stipulating certain variations to the standard specification. One of these was intricate fine cut lugs although it looks as though Pat, or the builder who was possibly either Les Ephgrave or Tom Board, insisted upon the powerful plain spearpoint (Cinelli?) 66mm bottom bracket shell because Phil was a very stocky person who could probably stamp a lesser B/B out of track. The other main variation (at least from the catalogue shown in Classic Lightweights) Phil apparently chose was to have oval fork blades, presumably because most of the use was to be on the road rather than the track.

Although the frame is still in its original finish there is no decal indicating the manufacture of the tubing. I’m still in touch with Phil who now lives with his family in Telford. He says he can remember little of the frame now but was able to disclose that the tubing was Columbus. Likewise, there is no serial number anywhere on the frame but the steering column shows it clearly as 01464. I don’t know what lugs were used (except perhaps the BB shell – see above). The front ends are Simplex with mudguard eyes and Campag rear end.

The frame size is 22.5 inches, top tube 22 in, nominal wheelbase 40.5 in, bottom bracket height (with sprints) 10.5 in. I haven’t checked the angles but, judging by the short top tube it’s probably something like 73 degrees parallel.

I was interested in the recent feature on Pat Hanlon as I owned an early model (frame number 259) that was acquired second hand by my older brother as a Christmas present for me in 1962, my brother being a keen cyclist and member of the Cambrian Wheelers bought it for me as an incentive to join a cycling club I have attached a couple of photo’s taken in the mid 1960’s when it was used it for commuting and racing etc.

I rode and raced on the bike for twenty years before selling it and buying a fancy Italian job…….an impulse sale that I quickly regretted and have often wondered if it was still around

Posted: Thursday 04th June 2020

Contents

- Overview

- Pat Hanlon Cycles Introduction

- Wheel builder for Macleans

- Early models

- A rare SWB Pat Hanlon image

- More information on Pat

- Pat Cycles more images

- Further information

- Advert

- First UK rider image

- Mick Butler

- Geoffrey Rubins

- PAT HANLON image

- More Information

- Word of mouth

- High demand

- Pat remarried

- John Basell

- Frame images

- Family Information

- Frame image

- More frame information

- More frame images

- Griff King-Spooner

- Griff King image

- Fancy Italian job

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.