The Match Sprint - Aristocrat of 20c summer outdoor track racing

Posted: Sunday 16th August 2020

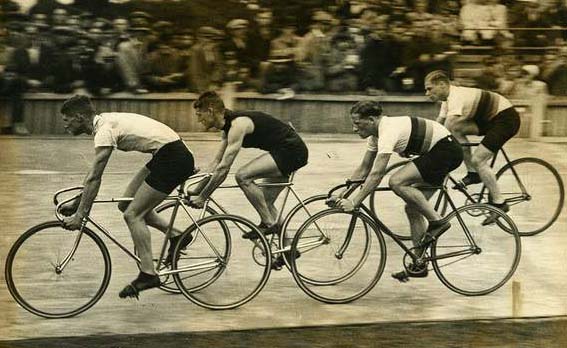

‘ In the 1000 meter match sprint…several riders start at once and the winner is the one who crosses the line first, no matter how long it takes. Time is taken on the last 200 meters of the ride, but this time is not used for any judging purposes. Sprints are a process of elimination and the winner advances through heats to quarter–finals, semi–finals, and so on. Early heats often pit three or four riders against each other, but the finals are always one against one.’ Jack Simes, Winning Bicycle Racing. (1976:125).

‘The sprint is the most subtle form of track competition…Sprinters will bring their bikes to a complete standstill in an attempt to force the other man to lead, or they will climb and dive on the banking to test his skill…when a sprinter does make a break for it he puts all his considerable strength into the “jump” – a burst of high–speed pedalling that takes him towards the line at forty miles an hour, head down, back arched, in an explosion of total effort.’ Roderick Watson & Martin Gray, The Penguin Book of the Bicycle. (1978: 238–240).

In his autobiography the legendary 20th century British match sprint champion Reg Harris recounts details of his track racing career, starting immediately before World War II and then peaking in the post–war period up until his retirement in the late 1950s. It is a story of an almost constant round of sprint racing at meetings held on dedicated banked outdoor cycling tracks in both Britain and on the Continent as well as in Australia in successive summers. Harris tells of his competing at race meetings both minor and major, of the 1948 London Olympics, of amateurs and professionals, of UCI world track championships contested in various countries every August, of post–world championship ‘revenge’ track meetings, of prestigious local events and of the match sprint ‘grand prix’ titles of capital cities like London, Paris and Copenhagen.

But this world which Harris (who died in 1992 aged 72) vividly describes and which he himself graced has long since disappeared. With few exceptions the outdoor tracks of his era either have since been demolished or are currently decaying. The summer outdoor track meetings once regularly held on them are consequently now a rarity and outdoor track racing specialists like him are a largely forgotten species.

Nevertheless, summer cycle racing on dedicated outdoor tracks has a long history stretching back to the very beginnings of competitive cycling in the late 19th century. Moreover, from early on match sprinting emerged as the unchallenged ‘aristocrat’ of summer outdoor track racing: it rapidly became and remained the centrepiece around which both entire summer track seasons and individual track meetings were organised for much of the 20th century; its leading exponents were the cycling superstars of their day; it was a magnet for sponsors; it provided its champions with exciting and rewarding sporting careers; and it profoundly influenced the design ethos of racing machines and equipment.

Summer outdoor track racing in the late Victorian and belle époque eras

In the late 19th century the cycling craze swept across North America, the British Isles, continental Europe and also European colonies overseas. It precipitated public interest in organised cycle racing which rapidly emerged as a popular spectator sport. Dedicated outdoor oval banked cycle racing tracks, complete with provision for substantial numbers of spectators, became a feature of many cities and towns. Often these were constructed by local entrepreneurs keen to profit from the new public interest in cycling competitions. In the United States, for instance, according to Aronson (1968: 300).

Elsewhere, this period saw the creation of such legendary summer outdoor tracks as Herne Hill in London (1891), Fallowfield in Manchester (1892) and the Buffalo velodrome in Paris (1893).

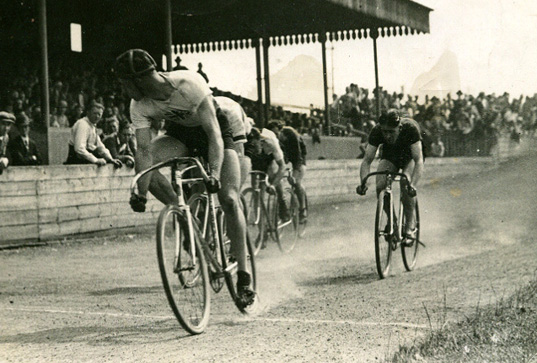

The events staged on these large early outdoor tracks – most were around 440 yards per lap or more – were many and varied as promoters vied for crowd–pleasing formulas. Longer–distance paced racing using human powered tandems (and sometimes also triplets, quads and quints) to pace individual competitors was but one variant. Shorter distance events involved groups of riders – ‘bunches’ – contesting distances based on the Imperial mile in Anglophone countries or the metric Kilometre in continental Europe.

Handicap races in which individual riders started simultaneously at staggered intervals around the track and the winner was the first to cross the finish line also figured prominently. It was in this context that the ‘match sprint’ event evolved.

Certain types of track events rapidly became standard features at 19th century track meetings. This process of standardisation was undoubtedly facilitated by the emergence of national and international associations for the administration of cycle sport. Bodies like the aforementioned ‘League of American Wheelmen’ in the USA (est. 1880) and the ‘National Cycling Union’ in Britain (est.1881) played key roles in this process by codifying racing rules and according selected events ‘national championship’ status. In 1892, the ‘International Cycling Association’ (ICA) was founded by representatives from Canada, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Holland, and the United States. Starting in 1893, the ICA instituted annual official world championship meetings, the first being held in the then burgeoning multicultural industrial city of Chicago in the USA to coincide with its ‘World Fair’.

While the exact rules under which it was ridden are unclear, the ‘amateur sprint’ world title was first contested in 1893 at these inaugural world championships pointing to its long and distinguished history. The winner of this first world sprint title was the American, A.A. Zimmermann (image left). ‘Zimmy’ was already an established international star for, to quote the distinguished 20th century cycling scribe, J.B. Wadley (1975:10):

‘it was on a new Safety Bicycle that Arthur Augustus Zimmermann of New Jersey carried all before him on a sensational 1892 European visit during which he won the one–mile, 5–mile and 50–mile championships of Great Britain.’ An American author observes:

‘Zimmermann was the Di Maggio of bicycle racing, and the idol of a considerable segment of American youth. His speed on the wheel earned him $40, 000 annually.’ Aronson, 1968: 300).

Noted for his both his celebrity lifestyle and rapid pedalling style, according to one legend (dismissed as being a myth by some) ‘Zimmy’ was capable of achieving a final 220 yards time of 12 secs. on a 68” gear at cadences of between 120 and 190 rpm. Whatever the case, Zimmermann quickly emerged as the world’s first sprint superstar, turning professional for Raleigh in the 1890s and subsequently winning events at track meetings across the US, Britain, Europe and Australia. He is said to have won over 1 000 races during his career and to have broken many records in the process. He retired from competitive cycling in 1905 and died in the US in 1936 at the age of 67.

In 1895 the ICA first introduced a match sprint event for professionals into the annual world championships to complement the amateur title. By this time Zimmy had turned professional while, according to Fotheringham (2010: 404):

‘(In the US alone) there were 600 professionals competing in track races at the end of the nineteenth century Crowds of up to 20 000 attended track races.’

Amongst the most unique of these early track stars was Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor, an African–American who turned professional in 1896 and won the world pro sprint championship in 1899 when the world championships were held in Canada. He subsequently raced successfully in Europe and Australia but after enduring persistent racism in the US he finally retired in 1910. A type of adjustable track handlebar stem with an underslung clamp was long referred to as a ‘Major Taylor’ in his honour as the machines which he rode were the first to be fitted with these. Taylor himself died in poverty in Chicago in 1932, aged 54, and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Thus, as Wadley (1975:11) observes:

‘Just as the basic design of the bicycle had been established by the turn of the century, the broad lines of international competition were also laid down.’

In 1900 however, following internal disputes, the ICA world governing body was disbanded and superseded by the ‘Union Cycliste Internationale’ (UCI). The UCI assumed responsibility both for legislating on international racing rules and for holding annual world championships. In the process, the epicentre of competitive cycling shifted from North America to Europe where it was to remain for the rest of the 20th century. Seemingly it was during this belle époque era immediately preceding World War I that the rules for contesting the match sprint event assumed their modern form. Nevertheless, the match sprint’s still fragile status as an established championship event is suggested by its not being included in either the 1908 London Olympics or the Stockholm Games in 1912 (which had no track events), although both the amateur and professional versions of the match sprint featured in every one of the annual UCI world championships held between 1900 and 1913.

But the world championships held between 1900 and 1913 also saw the emergence of a new sprinting phenomenon, namely the world championship match sprint title multi–winner who dominated the discipline for an extended period. The first to achieve this was the Danish rider, Thorwald Ellegaard, who won the world professional title a total of six times in an eleven year period (’01–’03;’06; ’08; ’11). In the amateur ranks the British rider, W.W.(‘Bill’) Bailey, proved to be the dominant sprinter in the latter part of this period, being world champion on no fewer than four occasions (’09–’11; ’13).

From the very beginning, sprinters attracted sponsorship, usually from within the ranks of the cycle industry. The Raleigh company was first and foremost in this regard, sponsoring Zimmermann in the 1890s as well as boasting of supporting top sprinters of the day in Italy, Austria and South Africa. Track meeting promoters also paid top sprinters handsome ‘appearance money’ with the likes of Zimmermann ‘asking that his contracts in Paris be paid in gold’ (Fotheringham, 2010: 439–440).

However, the outbreak of World War I terminated all international competitive cycling and decimated the ranks of riders. Few pre–war cyclists who survived the conflict returned to top level competition thereafter. To all intents and purposes, therefore, WW I marked the end of an era in track racing in general and in match sprinting in particular.

Match sprinting in the inter–war years: 1920–1939

When, in the inter–war period, summer outdoor track racing revived it was to remain concentrated almost exclusively in Europe. World championships were held at different venues throughout continental Europe, traditionally in August, with Britain being the venue only once – in 1922, when Britain’s H. ‘Tiny’ Johnson (so–called because at 5’ 4’’ tall he was unusually diminutive for a sprinter) won the amateur sprint title. The only other Anglophone title holder of this era was the Australian, Bob Spears, who took the world professional sprint championship crown in 1920.

During this period the track worlds were held on a total of three occasions in each of five European countries: Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy and Switzerland. They were staged twice in both Germany and Holland. Only with the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics did international (amateur) match sprinting leave the ‘Old World’, albeit briefly. This was in marked contrast to the situation pre–WW I when the world championships were held in North America on three occasions (1893, 1899 and 1912).

Not surprisingly given these circumstances, riders from three European nations in particular – Holland, France and Belgium – dominated international match sprinting, both amateur and professional, in the inter–war period. Holland won a combined amateur–professional total of 14 world sprint titles, France 7 and Belgium 6. During the 1920s the dominant professional match sprinter was the Dutchman, Piet(er) Moeskops, who was world pro champion five times, from 1921 to 1924 and then again in 1926. He was succeeded by the Frenchman, Lucièn Michard, who was the world amateur sprint champion in 1923 and 1924 (when he also won the sprint title at the Paris Olympics held, unusually, on the indoor Vel d’Hiv track) and then took the pro world title four times (1927–1930). During the 1930s it was the Belgian, Jef Scherens, nicknamed ‘Poeske’ (Flemish for cat) because of his uncanny ability to pounce at the last moment to beat opponents, who dominated the professional sprint scene, winning the world title six times (1932–1937). Remarkably, Scherens (after whom a noted brand of racing sprint rim was named) returned after WW II to win the world pro sprint title again in 1947 at the age of 38.

Thus the pattern established during the early 20th century, pre–WW I, when match sprinting at the highest level was dominated for an extended period by one particular rider (Bailey amongst the amateurs; Ellegaard amongst the professionals) was repeated once more during the inter–war period.

However, this is not to suggest that other top sprinters of this era did not come to enjoy celebrity status. One who definitely did was the German, Toni Merkens, the 1935 world amateur sprint champion, who won the Olympic sprint title in Berlin at the ominous1936 Games under controversial circumstances from the celebrated Dutchman, Arie Van Vliet (amateur world sprint champion in 1936, world pro sprint champion in 1938, 1948 and 1953 [this last at age 37]). Pre–WW II, Merkens frequently competed in track races in Britain where he was a great crowd favourite and, after turning professional, raced for the Hetchins marque (using his trademark ‘drooping’ stem) in London six–day events.

However, the Olympic Games and the UCI world championships were not the only prestigious international match sprint events to be contested during this period. The sprint ‘grand prix’ titles of major cities like London, Paris, Zurich and Copenhagen were distinctive in that they were track meetings at which the programmes were organised entirely around the deciding of these titles. Furthermore, these were ‘open’ events, allowing amateur and professional sprinters to compete freely against one other. This was something which was not permitted at either UCI world championships or Olympic Games during this period. The sprint grand prix meetings thus pitted the best sprinters in the world against each other regardless of their ‘official’ UCI status, allowing their relative merits to be critically assessed.

In addition to these varied types of international competition, in all the countries of the world where track cycling was then practiced, national and regional sprint titles were contested annually. These in turn served as vital ‘feeders’ to international sprint competitions with their winners being selected to compete variously in Commonwealth (then known as ‘Empire’) Games, Olympic Games and UCI World Championships. In the process, riders honed their sprinting skills while travelling extensively at a time long before foreign travel, sporting or otherwise, was commonplace.

All this served to set match sprinters largely apart from most other cyclists and enabled the best amongst them to informally organise themselves into a highly exclusive ‘sprinter’s club’. In so doing, they were able to negotiate favourable contracts with both race promoters and prominent producers of lightweight cycles and equipment. This was done either covertly in the case of amateurs or overtly by the professionals. Thus, for example, the champion British amateur sprinter of the 1930s, Bill Maxfield, was ‘employed’ by Claud Butler while earlier in the decade Maurice Selbach had provided his distinctive gold–coloured machines to many leading British and Commonwealth trackmen. The ‘Constrictor’ tyre and component company, headed by the former multi–world track champion, Leon Meredith (1883–1930), also did much to promote inter–war track racing in Britain.

However, World War II put an end to all international cycle sport for the duration.

Post–World War II: Match sprinting enters the ‘Reg Harris era’

In contrast to the situation after WW I, immediately following the end of WW II a number of the leading pre–war sprinters who had survived the war years resumed competition. (Toni Merkens was not amongst them – he was killed in 1944 fighting for the German army on the Russian front). His fellow German, Alfred Richter [1932 world amateur sprint champion riding a Selbach] who opposed the Nazis, mysteriously died in 1940 while in the hands of the Gestapo after apparently being betrayed by other German cyclists). Former world champions who did return to racing included Jef Scherens, Louis ‘Toto’ Gérardin of France (world amateur sprint title holder, 1930), Arie Van Vliet and fellow Dutchman Jan Derksen (world amateur sprint titleholder, 1939) all of whom were by now established professionals.

Simultaneously, amateur sprinting’s ranks were boosted by an influx of a new generation of riders anxious to prove themselves now that the war was over. They included the Swiss sprinter Oscar Plattner, Sid Patterson from Australia, Italian prodigy Mario Ghella and Britain’s Reg Harris. With most soon to turn professional and challenge the ‘old order’ of the professional game the stage was set for the 1950s to become a new ‘golden age’ of match sprinting reminiscent of the pre–WW I era of Zimmy, Major Taylor, Bill Bailey and Thorwald Ellegaard.

Due to the war, however, the ages of the leading sprinters of this period, both amateur and professional, varied widely. Some, like Ghella, were teenagers; others like Harris were war veterans in their late ‘twenties; others again like Gérardin, Derksen and Van Vliet were well into their ‘thirties, having survived the Nazi occupation of their countries. These differences both in ages and wartime experiences combined to form a volatile mixture which undoubtedly served to intensify their subsequent on–track rivalries.

Harris created a sensation in Britain in 1947 when he won the world amateur match sprint title on the massive 660 metres per lap outdoor Parc des Princes track in Paris. He was the first British rider to win the world title since ‘Tiny’ Johnson had done so 25 years earlier in 1922. In Harris post–war Britain thus had a new national sporting hero and the British public fully expected him to triumph again in the sprint event at the 1948 London Olympics.

However, this was not to be for the 28–year old Harris was beaten in two straight races in the Olympic sprint final by the baby–faced 18–year old Italian, Mario Ghella. (Legend has it that, in a piece of sprinter’s ‘mind–gamesmanship’, after first warming up on rollers Ghella had himself physically carried to the start line by his Italian minders where Harris was already poised waiting prior to each leg of the final). Stung by his Olympic defeat Harris responded by immediately turning professional and, now openly sponsored by Raleigh (who had succeeded Claud Butler as his covert sponsor before the Olympics), he embarked upon a full–blooded assault on pro sprinting’s ‘old guard’.

In British cycling circles today the 1950s are still commonly referred to as the ‘Reg Harris era’ because of his domination of the sport at that time. Harris proceeded to win the world professional match sprint title for three years in succession (1949–1951) and then again in 1954. Watched eagerly by large crowds, he engaged in a succession of titanic match sprint battles on tracks throughout both Britain and Europe, most notably with the ageing Van Vliet but also with Plattner, Derksen, Gérardin and a host of other minor sprinters. Harris’ heroic achievements stimulated British interest in match sprinting in others and in 1954, when Harris himself won the professional world sprint title for the fourth (and last) time, the amateur event was won by his fellow–countryman, Cyril Peacock.

Peacock subsequently turned professional and like Harris was sponsored by Raleigh after having previously been supported as an amateur by Carlton. But Harris precipitously decided to retire at the end of1957 at the age of 37. He did so after being eliminated by the physically compact but wily and acrobatic French sprinter, Roger Gaignard, in the early rounds of the world championships held that year on the ageing and decrepit Rocourt track in Liege, Belgium (The UCI nevertheless saw fit to use this ‘venue’ once again for the world track championships in 1975, when Daniel Morelon [France] and John Nicholson [Australia] respectively won the amateur and professional sprint titles, by which time the stadium was a sporting slum).

Of his decision to retire, Harris subsequently wrote in his autobiography:

‘I suppose I was getting a little older by 1957 and in my case, instead of manifesting itself in a lack of speed or a lack of strength, the effect of my years was to make me just a little inconsistent. One might almost say that Van Vliet’s Achilles’ heel had caught up with me. After the championships I returned to England briefly, and then embarked on a series of revenge races all over Europe and North Africa…I beat the world champion, Derksen, in Copenhagen. In so doing, I set the fastest time over 200 metres. My 10.9 seconds caused a sensation. I hung up my track frames at the end of October and Arie Van Vliet [aged 41] did the same four months later. That left Jan Derksen not only champion of the world, but by far the greatest sprinter in existence.’ Reg Harris, Two Wheels to the Top (1976: 150–1).

Harris’ retirement, along with Van Vliet’s, marked the end of an era in the history of match sprinting on outdoor tracks in the summers of the 20th century.

The 1960s: Twilight of summer outdoor track racing

In 1970 the UCI world track championships were held on the outdoor Saffron Lane track in Leicester, England. Surprisingly, this was the first time that the worlds had been held in Britain since ‘Tiny’ Johnson won the world amateur sprint title in London nearly 50 years earlier in 1922. However, there were to be no British sprinting triumphs at Leicester: the amateur title was to be won decisively once again by the evergreen Frenchman, Daniel Morelon, the professional title by the Australian neopro, Gordon ‘Gordie’ Johnson.

In his Cycling Year Book (1971), N.G. Henderson both reports and reflects on the 1970 Leicester world championships and also includes an insightful piece by Gordie Johnson himself. Together these make for disturbing reading for any fan concerned with the fate of outdoor track racing. Henderson wrote:

‘Comments about the championships have been many and varied. Unhappily, the public was often ill–treated or ignored…the events were (also) partly unsuccessful…in the standard of riding and in the quality of entry in certain events…Why was the stadium almost empty?…weather, prices, lack of information…’(Henderson, 1971: 78–80)

The professional match sprint attracted a total of only 14 entrants. These did not include the 1969 title holder, Belgian Patrick Sercu (amateur winner in 1963; pro winner also in 1967), who by this time had opted for the far more rewarding combination of summer road racing alongside his compatriot Eddy Merckx and the winter six day circuit. Johnson won the pro title by beating the ageing Italian Santé Gaiardoni (pro world champion in 1963 after winning both the amateur world and Olympic sprint titles in 1960) in the final.

He had only recently turned professional for Carlton Cycles after finishing second in the sprint to fellow–Australian John Nicholson in the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh. At Leicester, however, in the amateur contest Nicholson could only finish fourth to the ‘eternal amateur’ Morelon who, apart from winning every one of his races on his way to his fourth world title, consistently set the fastest 200 metre times (around 11 seconds) of all the sprinters, amateur or professional, at the 1970 championships.

Henderson’s sombre conclusion after the Leicester worlds was that:

‘…every cycling enthusiast knows that the great days of track racing in Britain, when Herne Hill used to pack in thousands for duels between professional sprinters when they were really professionals – Harris, Van Vliet, Plattner and the like – are a thing of the past.’ (Henderson, 1971: 62).

It was certainly the case that, after Harris and Van Vliet had retired, two ‘sprinting schools’ came to dominate match sprinting at the highest levels in the late–1950s and the 1960s to the virtual exclusion of all others:

- The Milan–based ‘Vigorelli school’ of Italian sprinters (Sacchi, Maspes, Gasparella, Gaiardoni, Beghetto, Borghetti and Pettenella)

- The ‘French vitesse school’ of amateurs consisting of their brilliant coach, the ex–champion‘Toto’ Gérardin, and riders like Rousseau, Trentin and Morelon

Representatives of these two sprint ‘schools’ annexed almost all of the UCI world titles and Olympic titles contested during this period. In so doing, however, these events came to hold little interest for fans from other countries.

Thus, by the 1970s, summer outdoor track racing and with it match sprinting had become but a shadow of its former self. Nothing demonstrated this better than the 1975 UCI world track championships at the seedy Rocourt stadium in the run down Belgian mining town of Liege on the banks of the River Meuse…embarrassingly poorly hosted for the UCI by the Belgian LVB national body (which happily accepted sponsorship for the meeting from ‘Boule d’Or’ cigarettes), devoid of spectators, uninspired and pedestrian racing. The fans responded by voting with their feet. They went in their droves instead to watch the Dutchman, Hennie Kuiper, break away to win the 1975 world professional road race title on a tough course in the misty, hilly Belgian Ardennes, scene of the ‘Battle of the Bulge’ at the end of WW II.

By 1975, however, as the world championship track events in Liege showed, the battle for the survival of summer outdoor track racing and its centrepiece, the match sprint, was to all intents and purposes well and truly over.

Acknowledgements

I am particularly indebted to two sources:

Firstly, to N.G. Henderson for the carefully compiled and comprehensive record of world championship and Olympic results contained in his book Cycling Classics, 1970–72 (1973).

Secondly, to the Classic Lightweights website for its inspirational images and copy of classic track machines by the likes of Bates, Sibbit, Selbach, Carlton, Raleigh, Cinelli, Coppi, Claud Butler, and many others as well of track racing and track riders in the classic era.

Without these I would never have been able to pursue the theme of this article.

References

Aronson, S.H. (1968) ‘The Sociology of the Bicycle’. In M. Truzzi (ed.) Sociology and Everyday Life. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice–Hall.

Fotheringham, W. (2010) Cyclopedia: It’s all about the bike. London: Yellow Jersey Press.

Harris, R. [with G.H. Bowden] (1976) Two Wheels to the Top: The Autobiography of Reg Harris. London: W.H. Allen.

Henderson, N.G. (1971) Cycling Year Book. London: Pelham.

Henderson, N.G. (1973) Cycling Classics, 1970–72. London: Pelham.

Simes, J. [with B. George] (1976) Winning Bicycle Racing. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Wadley, J.B. (1975) Leisureguides: Cycling. London: Macmillan.

Watson, R. & M.Gray (1978) The Penguin Book of the Bicycle. London: Allen Lane.

Posted: Sunday 16th August 2020

This article appears in the following categories.

Upcoming Events

Whether you are looking for a gentle social meet up, or a 100-mile ride browse the community’s upcoming events and plan your next weekend outing.